Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

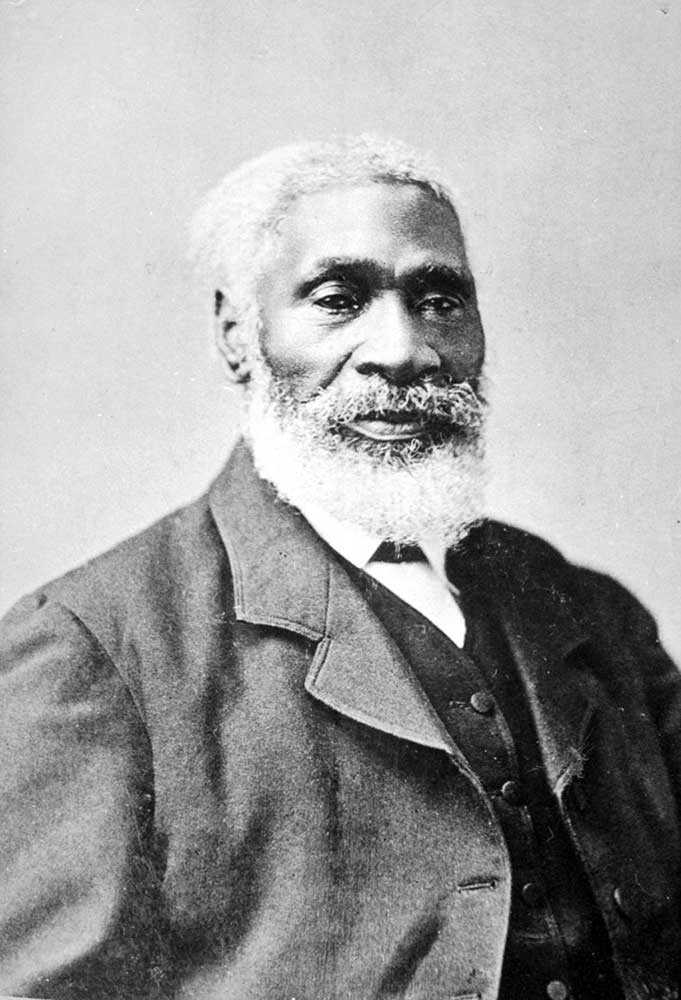

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

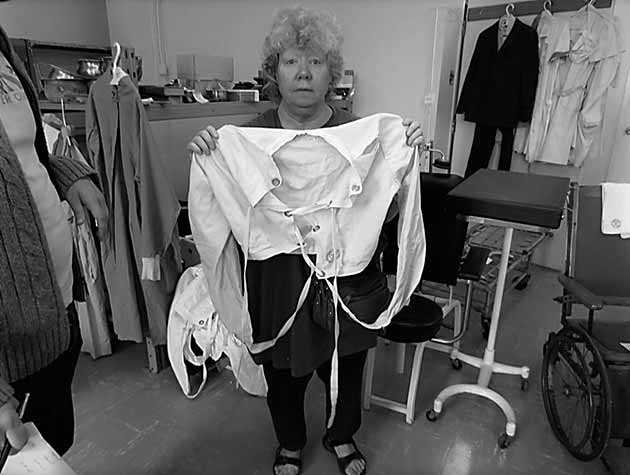

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

A prison town’s difficult heritage

Heritage is no longer solely the conservation and appreciation of the beauty, creativity and innovation of the past. Heritage now encompasses the scars of history, the physical sites of shame, and the intangible cultural memories of horror. This heritage is considered dark or difficult heritage, “heritage that hurts.” It is the heritage that reminds us of the pain and suffering of the past, forces us to bear witness to atrocities, and unsettles our understandings of our place in the world.

Kingston, a place where “history and innovation thrive,” is also a city with a dark history. Kingston was built on the penitentiary system, beginning with the opening of Kingston Penitentiary in 1835. The prisons have shaped the city’s development; these sinister sites are now part of the urban landscape. At one time, there were 10 active correctional institutions in Kingston and the surrounding area. As the sites of riots, deaths, trauma and abuse, Kingston’s prisons have been the focus of local and national attention for years. With the recent re-opening of the Kingston Penitentiary for public tours and the sale of the decommissioned Prison for Women to a private developer, the need respectfully and appropriately to preserve and confront this dark part of Kingston’s heritage is crucial.

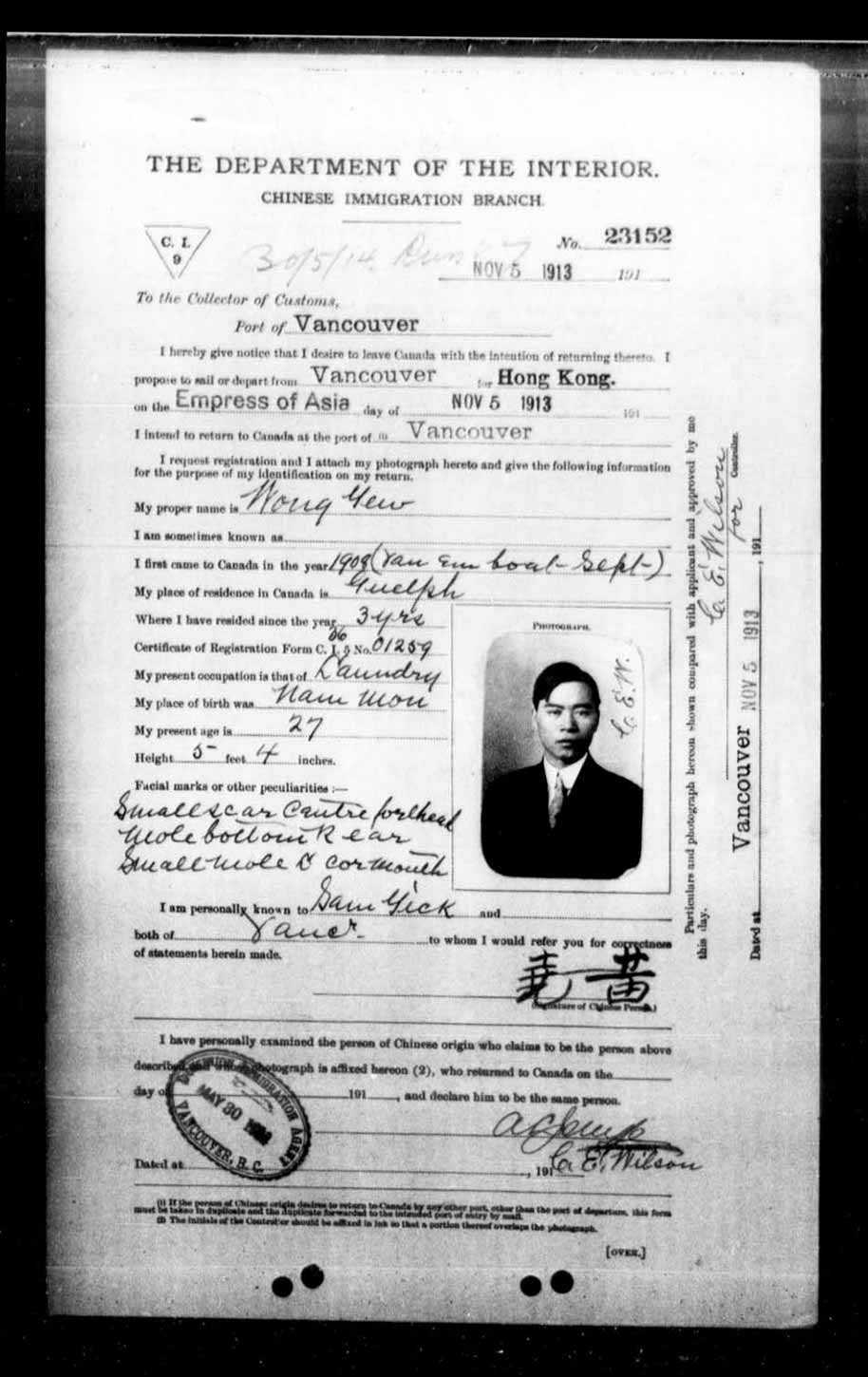

In Our Own Words: The Links Between Kingston’s Heritage and its Penitentiaries was an oral history project funded by the City of Kingston and the Friends of the Penitentiary Museum that explored the difficult heritage of Kingston’s penitentiaries. As the project’s Oral History Coordinator, I sought to examine the complex historical and cultural connections between the Kingston community and the city’s penitentiaries to understand how the presence of the penitentiaries shaped the local social fabric. Through the use of oral history interviews conducted with former and current Correctional Services Canada personnel, employees of affiliated businesses and volunteers with related organizations, previously incarcerated individuals, community members, and prisoner justice activists, this project aimed to capture the human experiences and personal relationships that developed in and beyond the foreboding limestone penitentiary walls, and the ways in which Kingstonians understand and negotiate the city’s difficult heritage as “Canada’s Penitentiary Capital.”

These oral histories ranged from nostalgic accounts of the institutions and discussions of the benefits that they have brought to Kingston to the self-reflexive, critical or jaded tales of the ways in which the penitentiaries have affected the individuals, families and the wider Kingston community. For many Kingstonians, the prisons generate complicated mixtures of emotions – pride, nostalgia, anger, shame, disgust – but for others, these institutions and their presence in Kingston often go unquestioned. The prisons are commonplace, part of the physical and cultural landscape. They’re “just there.”

Projects like In Our Own Words are crucial to capturing Kingston’s intangible heritage, especially the “heritage that hurts,” to stimulate nuanced dialogue and critical reflection, and to give voice to those whose stories are silenced in official narratives. The success of the St. Lawrence Parks Commission’s Kingston Penitentiary Tours demonstrates the great interest in Kingston’s penitentiary history and the need critically to consider the ways in which that dark heritage is presented and understood, especially in connection to “dark tourism.” As the commodification and consumption of dark heritage, dark tourism is defined as “the act of travel associated with death, suffering and the seemingly macabre” (according to Richard Sharpley, author of Shedding Light on Dark Tourism: An Introduction, in The Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism). The reasons for engaging in dark tourism vary and go beyond morbid curiosity. As scholars Erica Lehrer and Cynthia E. Milton explain, “[w]hile visits to sites of former atrocity raise concerns about voyeurism and crass commercialization, they may just as often draw people earnestly seeking to mediate on peace, imagine common futures, and even forge these through dialogue or political action” (from Introduction: Witnesses to Witnessing, in Curating Difficult Knowledge: Violent Paths in Public Places). As an avenue where dark heritage is disseminated, the Kingston Penitentiary Tours, in conjunction with projects such as In Our Own Words, have the potential to unsettle the “ordinariness” of Kingston’s prisons to provide a deeper, multi-vocal social history of Kingston’s penal past.