Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

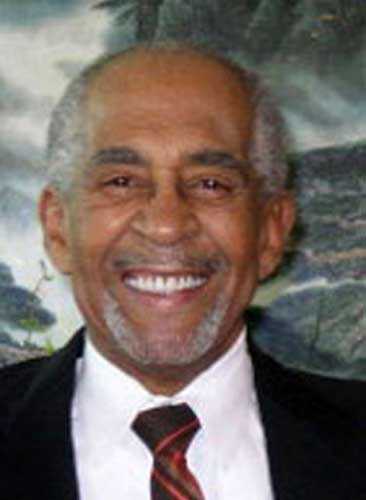

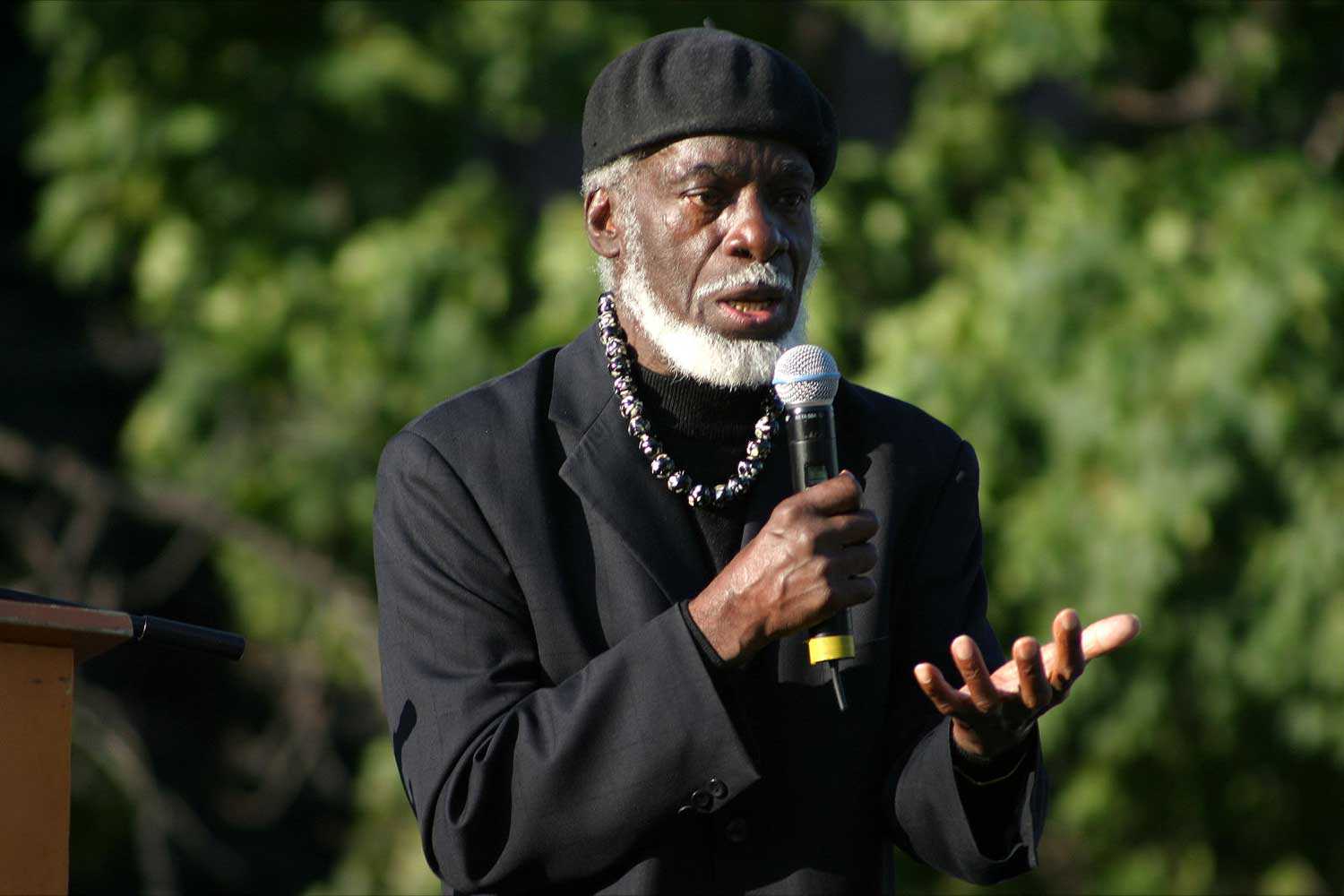

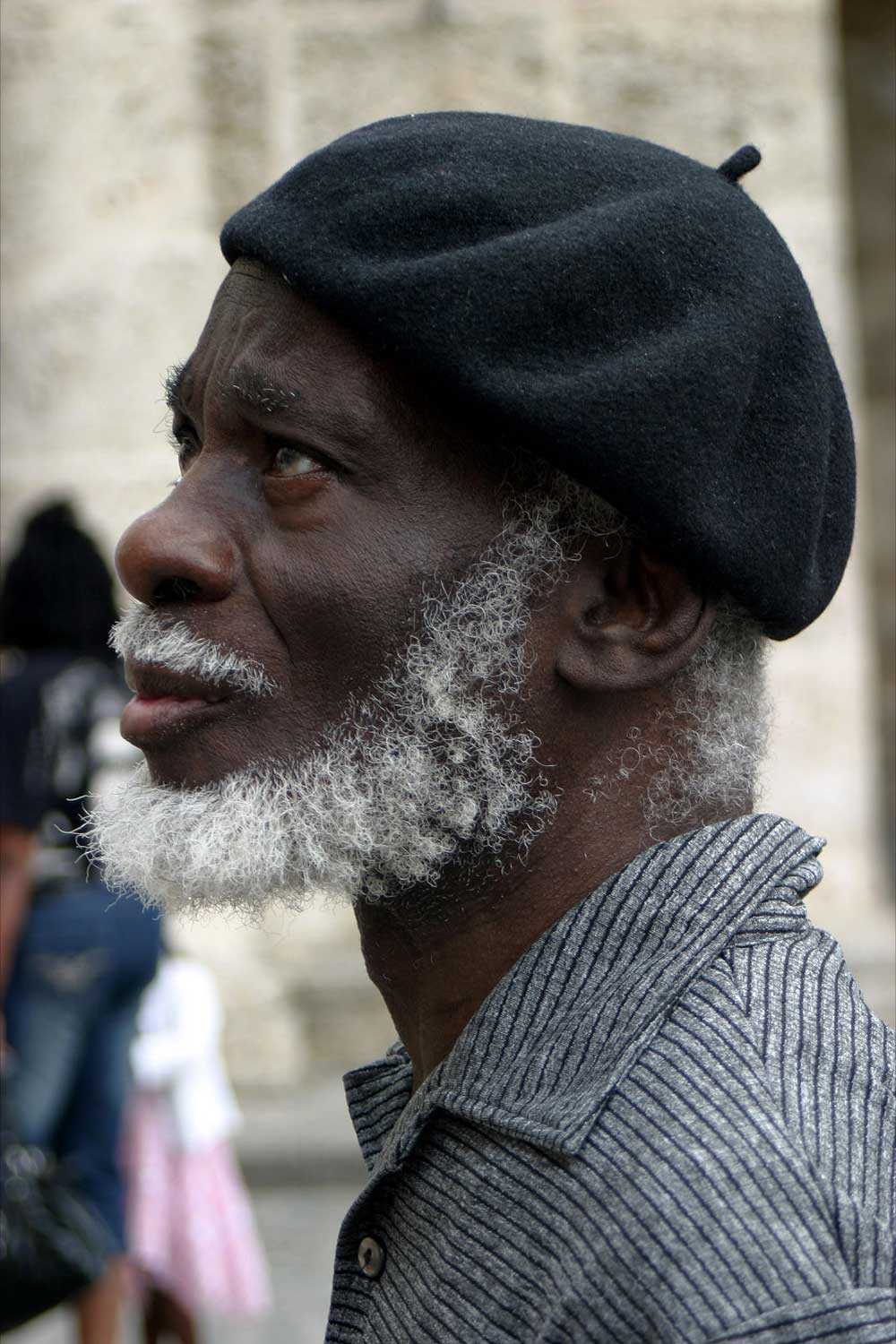

A tribute to Dudley Laws

In February 2011, Dudley Laws checked himself out of hospital against medical opinion to honour a commitment previously made to inmates at Joyceville Institution in Kingston, Ontario to participate in Black History Month celebrations. The following month, on the evening of March 23, Laws summoned a small cadre of community activists chiefly from the Black Action Defense Committee (BADC) to his hospital bedside for an urgent meeting.

Although terminally ill, Laws continued to address agenda items that he deemed unresolved. These two examples were fitting testaments of selflessness, an unwavering commitment and a steely discipline in the service of African people for over 50 years – from England to Canada. It became apparent to all in attendance on March 23 that, on being given assurances that the work was indeed carrying on, Laws was able to relent his physical struggle and, four hours later, died, leaving the Black community with a tremendous void.

Who then was Dudley Laws? From a practical perspective, he was a welder, a man of humble beginnings, the son of Ezekiel and Agatha Laws, hailing from Saint Thomas parish in Jamaica. He shared this birthplace with Paul Bogle, the Baptist deacon and national hero who fearlessly led ex-slaves on a march into Spanish Town in 1865 to present their discontent with the injustices of the colony.

Any attempt to write the history of Dudley Laws must include the history of the BADC. Although Laws was the charismatic and courageous leader of the organization, BADC has always been comprised of progressive elements of the African-Canadian community spanning generations, nationalities, gender and class. These elements helped to shape Law’s legacy by practicing the concept of the extended family.

There is a misconception that Laws and the BADC were singularly focused on issues of anti-Black racism. An accurate representation of history, however, will show several campaigns in coalition with the South Asian community, the Sikh community, the Filipino community, the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty, the Toronto Coalition Against Racism, First Nations and advocacy on behalf of many non-Black victims of police actions. Dudley Laws lived the political dictum of Martin Luther King Jr., who stated that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Laws had an excellent pulse of the community and was pragmatic in his approach to the myriad of problems that faced Black people. He recognized that times had changed, as had dynamics of community, and he was willing to work with new ideas, different people and in new ways. He was also open to working with all people – irrespective of age, ideological persuasion, dogma or cultural background – as long as the effort was sincere and about the inspiration of oppressed people.

It is also important to note that Dudley Laws cannot be defined solely by his political advocacy. He was also a keeper of culture and a man of song, poetry and dance. He could croon to the sounds of Louis Armstrong or Nat King Cole. He could go tête-à-tête against Renaissance men such as Milton Blake or Colin Kerr in reciting classical poetry and literature from memory. He could spar with his best friend Hewitt Loague to establish who had the smoothest moves and lightest feet on the dance floor in their sweet serenades of soul music. And, along with the late Jack Johnson, he played an important role in keeping alive the oral and social tradition of the wake. Rooted in Africa and the Caribbean, the wake is an important tradition that assists in the collective bereavement of loved ones by celebrating life, community and culture through ritual, food, drink and song.

In the final analysis, though, Dudley Laws and the BADC would triumph and be responsible for significant public policy reform, anti-racism legislation and the civilian overseeing of police agencies. More importantly, African-Canadians would be instilled with the necessary courage and belief that action and advocacy would bring about the necessary changes for equal rights and justice. This is the same premise in which 150 years ago the oppressed men and women of Morant Bay – the birthplace of Dudley Laws – would rise up to change the course of history for years to come.

![F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/27790_boy_and_woman_520-web.jpg)