Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Changing perspectives on the past

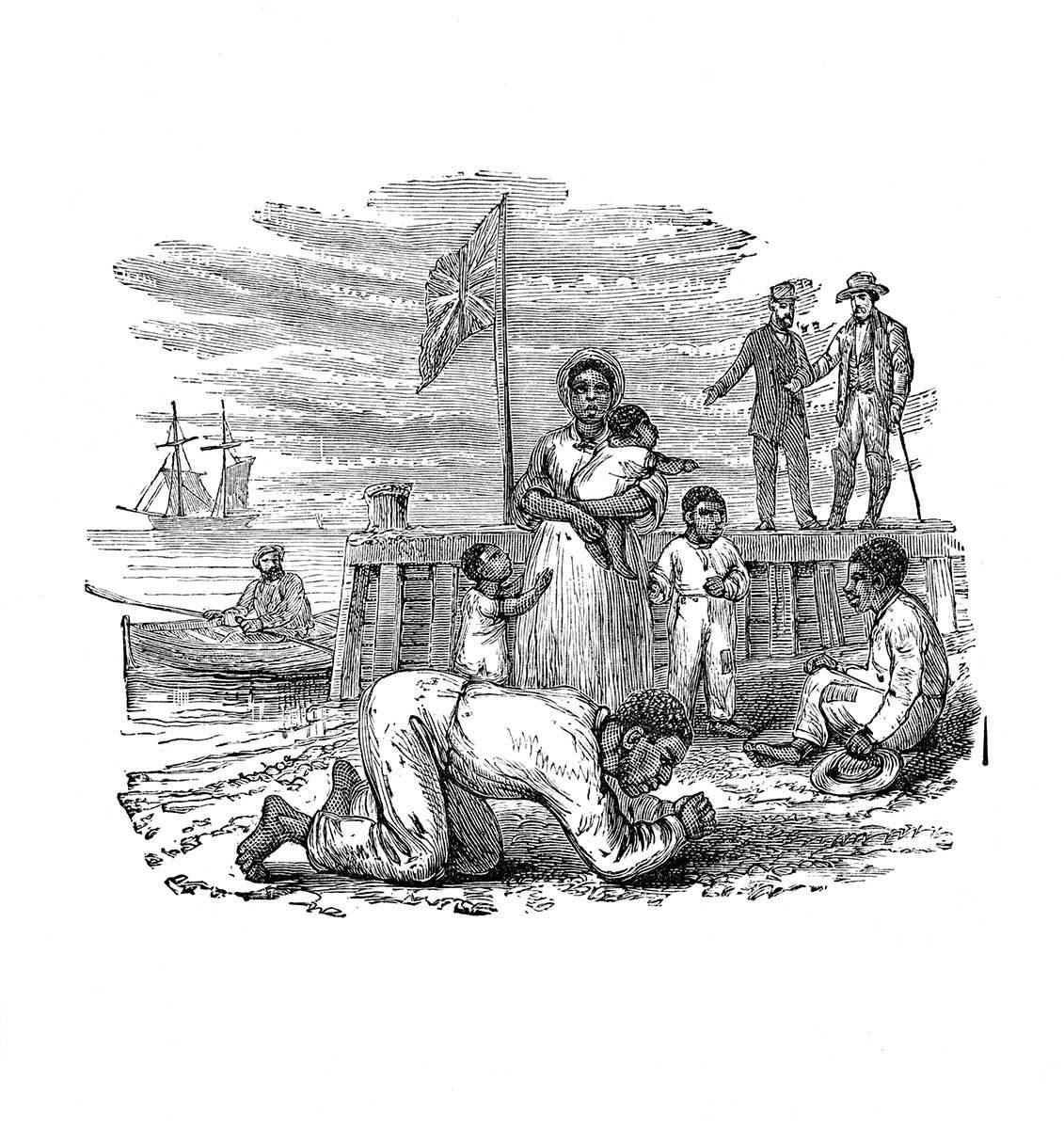

"Explore the Trust’s Online Plaque Guide at www.heritagetrust.on.ca/plaques-more. Or trace the perilous path of 19th-century Blacks as they fled to the sanctuary of the north along the silent tracks of the Underground Railroad by visiting www.heritagetrust.on.ca/slaverytofreedom."

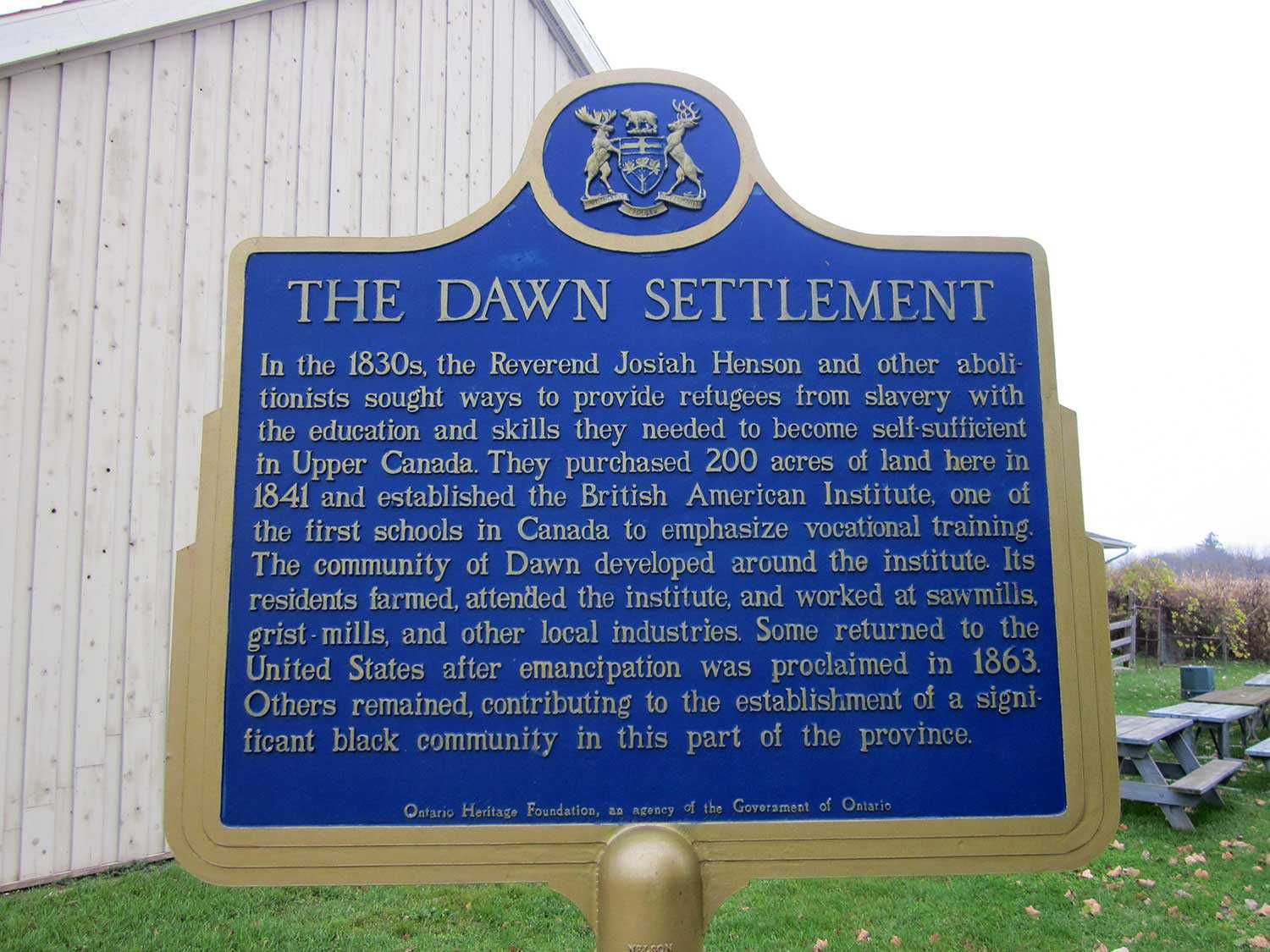

The Ontario Heritage Trust’s provincial plaque program has existed for more than 50 years. Throughout this time, it has commemorated several people, places and events relating to Ontario’s Black heritage. An examination of these plaques reveals that significant changes have occurred over time in the program’s approach to Black heritage – changes that are reflected in altered terminology, redirected emphasis and a growing number of provincial plaques that commemorate Black heritage.

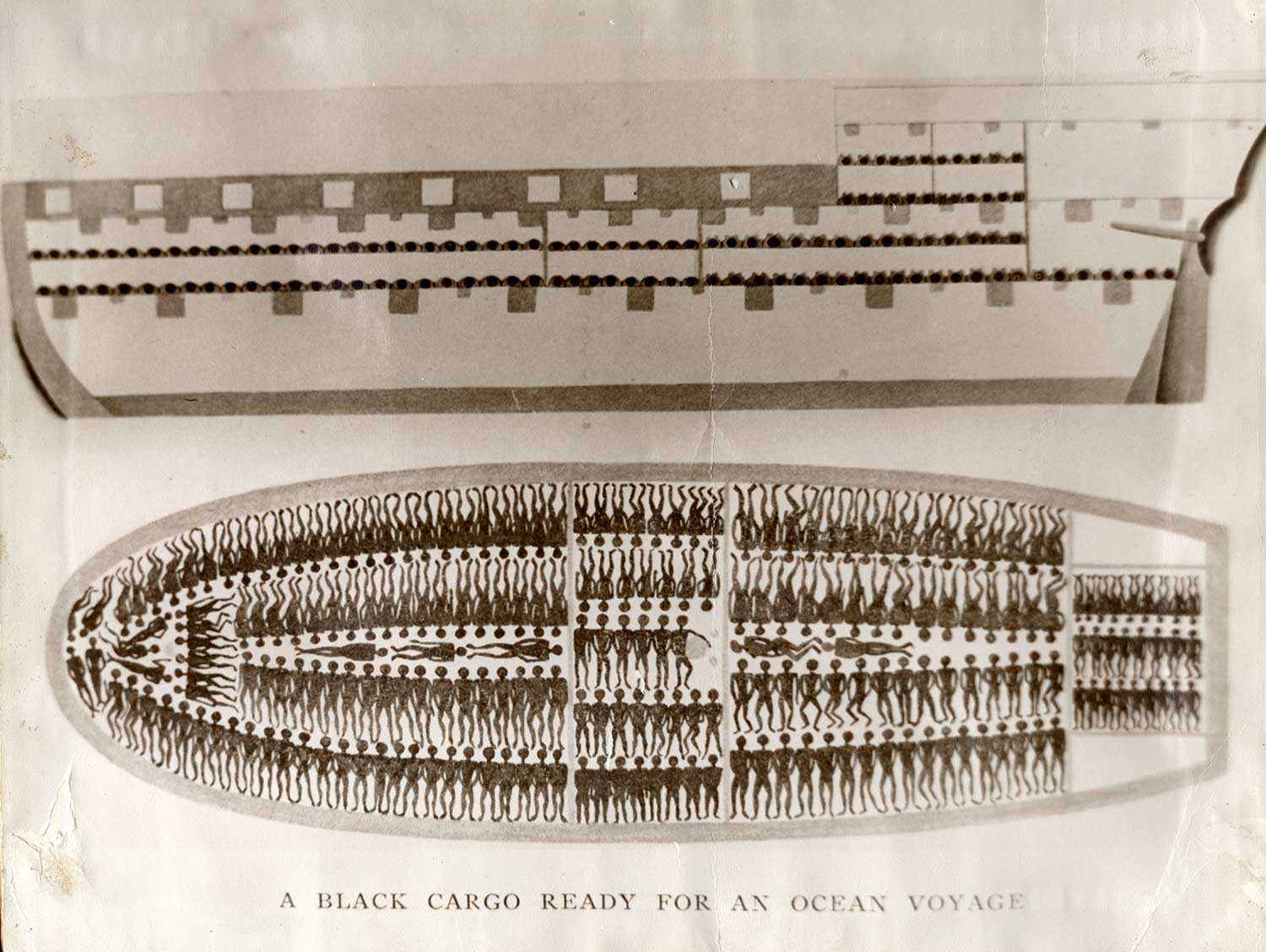

These shifts in approach to Black heritage – evident not only in the plaque program but in cultural, political, social and educational institutions throughout the province – have resulted from several often interconnected influences, including the civil rights movement, multiculturalism and post-colonialism. It is important to remember that greater Black heritage representation in plaques, and changes to the terminology used in plaque texts, are not ends in themselves, but are part of a wider process of reexamination.

Prior to the 1960s, the heritage landscape was dominated by the notion that a single overarching historical narrative could accurately and comprehensively explain who we were and where we came from. That single narrative was often both exclusionary (in that it overwhelmingly represented one dominant perspective) and inflexible (because history was viewed as something unalterable). There was a pervasive notion that things had either happened or not happened and could be described accurately or inaccurately. This imbued the historical narrative with claims to objectivity and authority that marginalized other perspectives – including those of Black Ontarians.

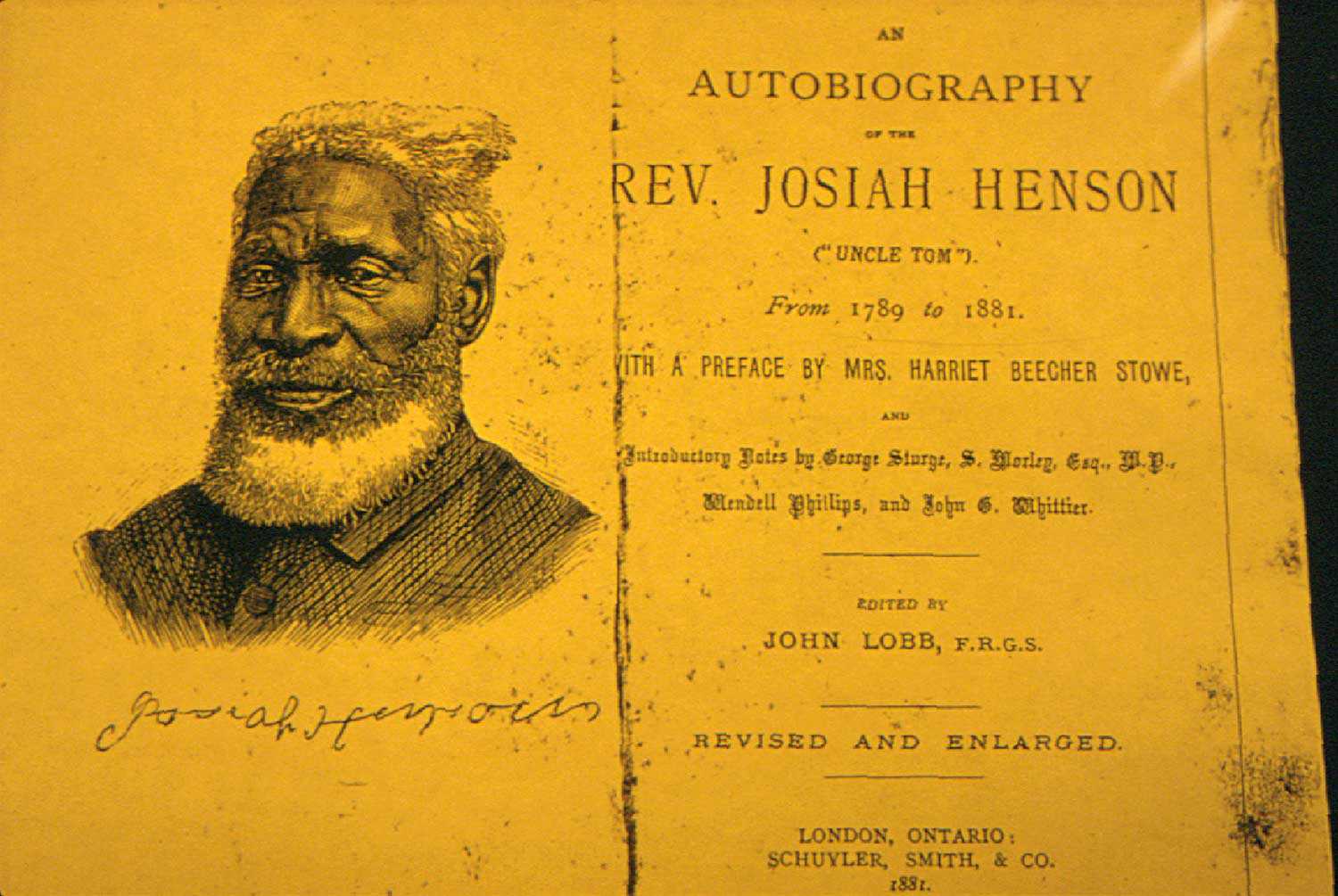

But, in recent decades, historians and scholars have peeled back the layers of these overarching historical narratives to reveal omissions, hierarchies, contradictions, distortions and motivations that operate within the narratives that were previously largely hidden or ignored. They have delved into the complicated anatomy of how histories, cultures and identities are constructed and have argued that the historical past is not something absolute and unalterable, but a sustained dialogue between past and present perspectives – in other words, an ongoing process.

International scholars such as Benedict Anderson, Edward Said, Arjun Appadurai and the Canadian, Charles Taylor, have emphasized the role of imagination in the construction of histories, identities and nationalities. This emphasis on imagination does not suggest that history is in any way make-believe or unreal, nor does it diminish the real impact that historical events have had on people. Instead, it reminds us that the historical past is something that we, in the present, invoke and frame. We bring our collective and individual imaginations to bear on past events by creating context, envisioning connections, filling in gaps, describing history with current terminology and projecting our own thoughts and experiences onto it.

As individuals, communities and societies have a degree of agency that we bring to the process of history creation – agency that can be used to change, broaden and diversify that process. With this in mind, concerted efforts have been made to redress imbalances in the way our history has been perceived and to make room for multiple voices and experiences – including those that have been previously marginalized. Changing approaches to Black heritage, evident in the provincial plaque program and elsewhere, reflect this spirit of pluralism.

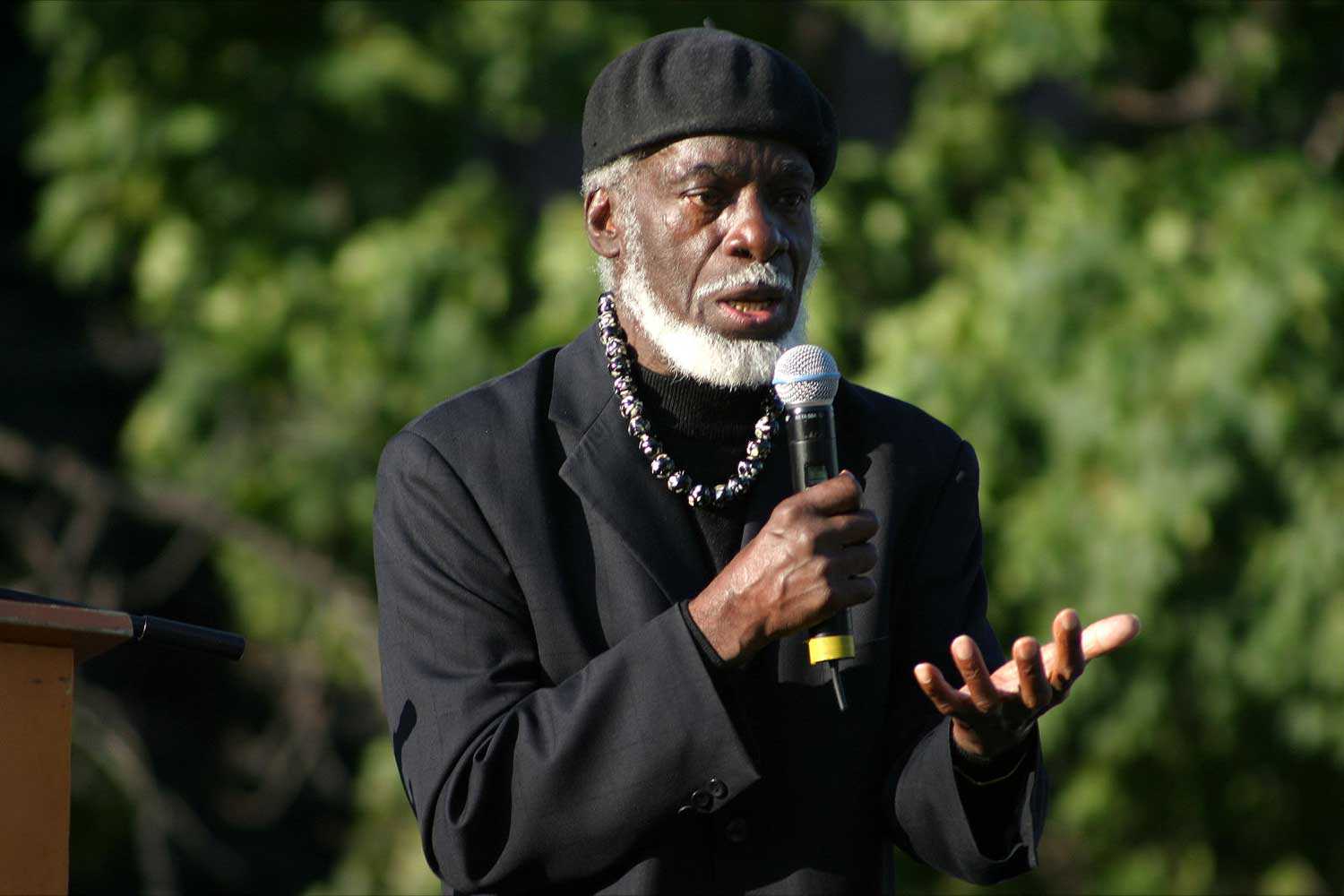

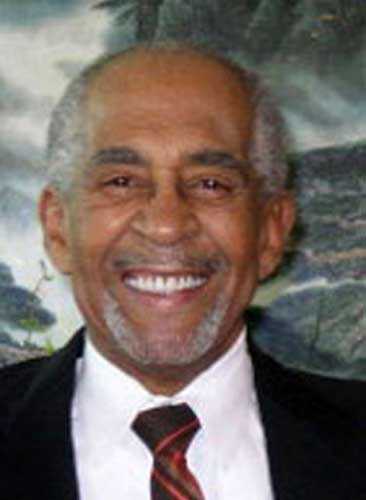

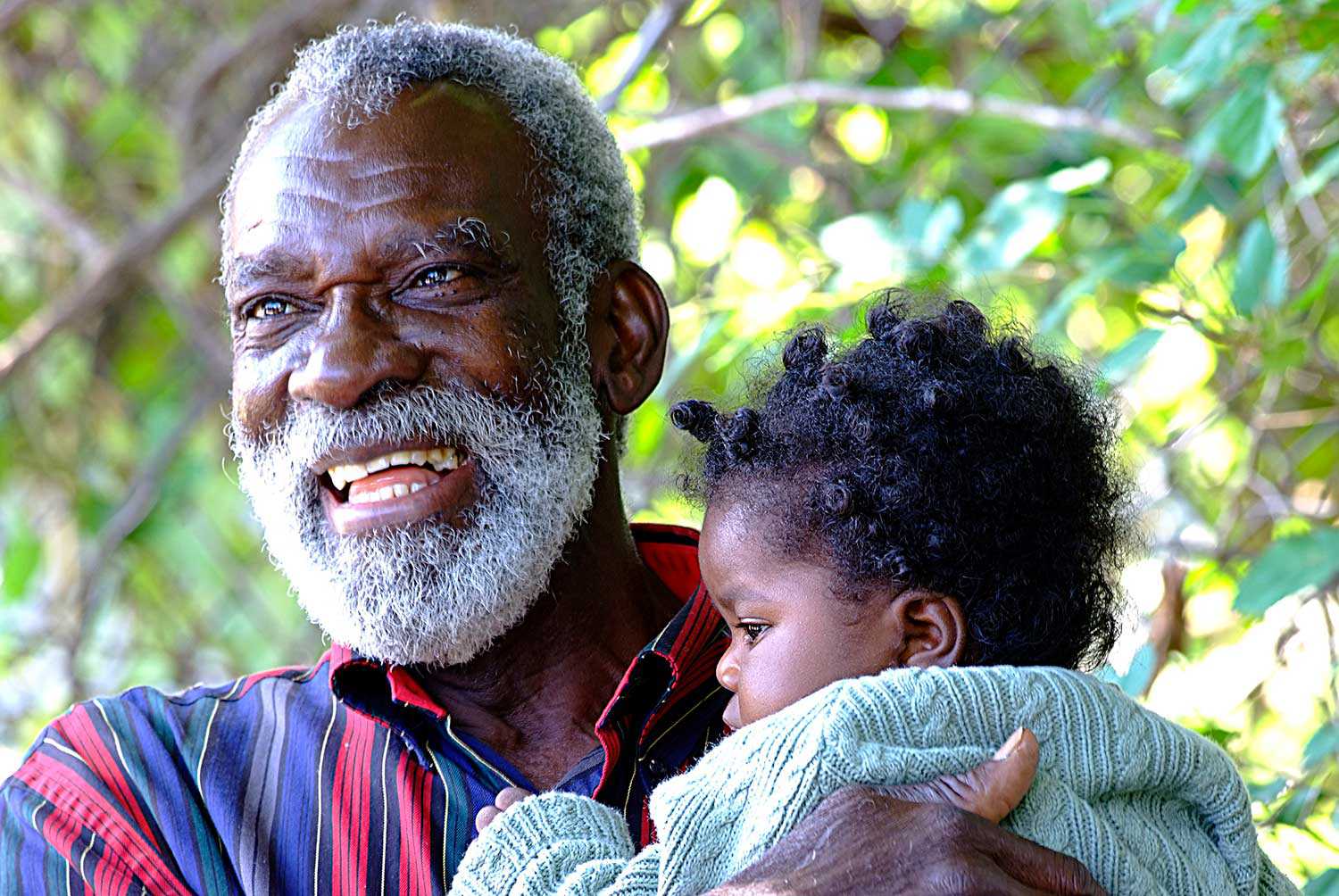

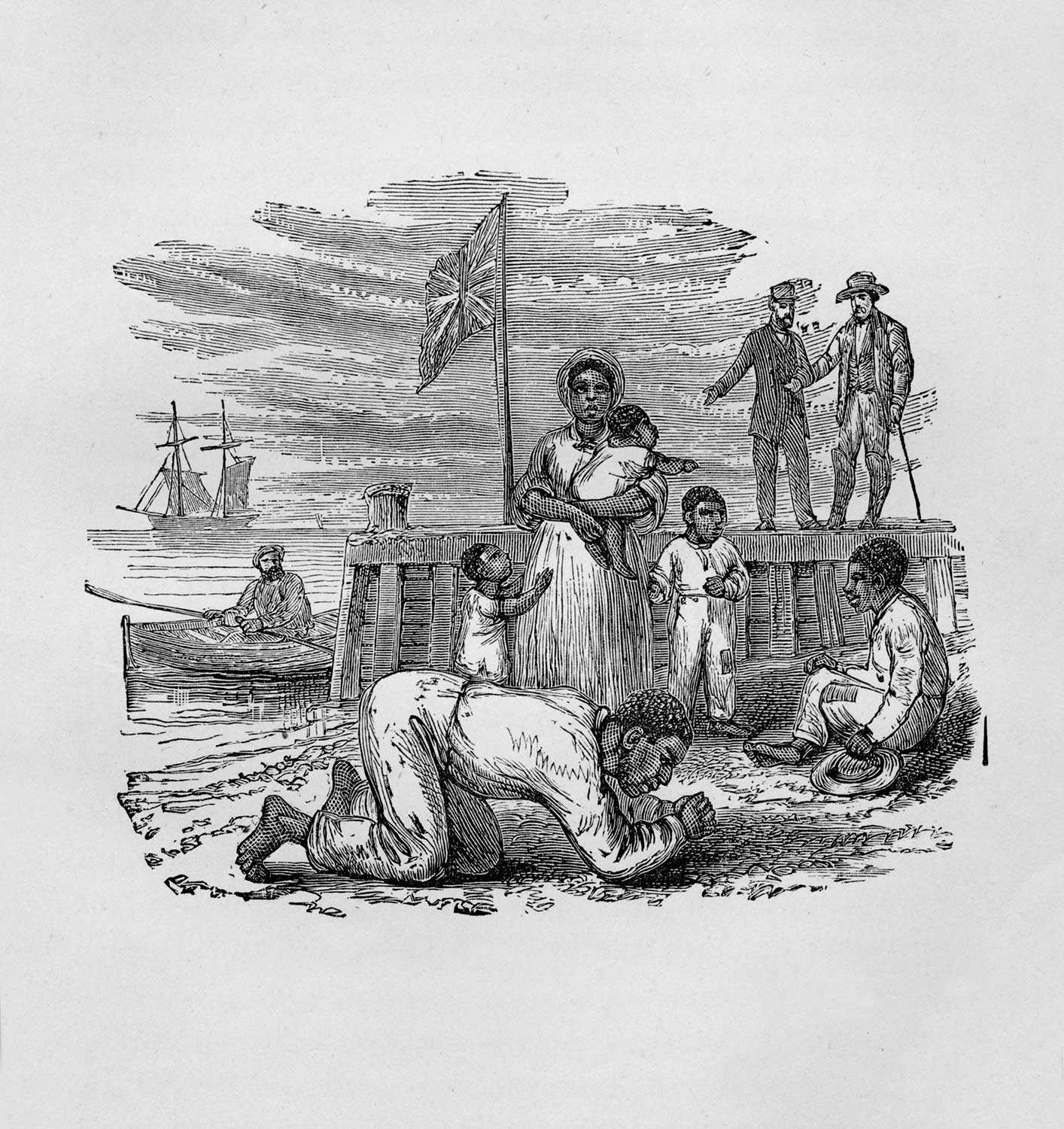

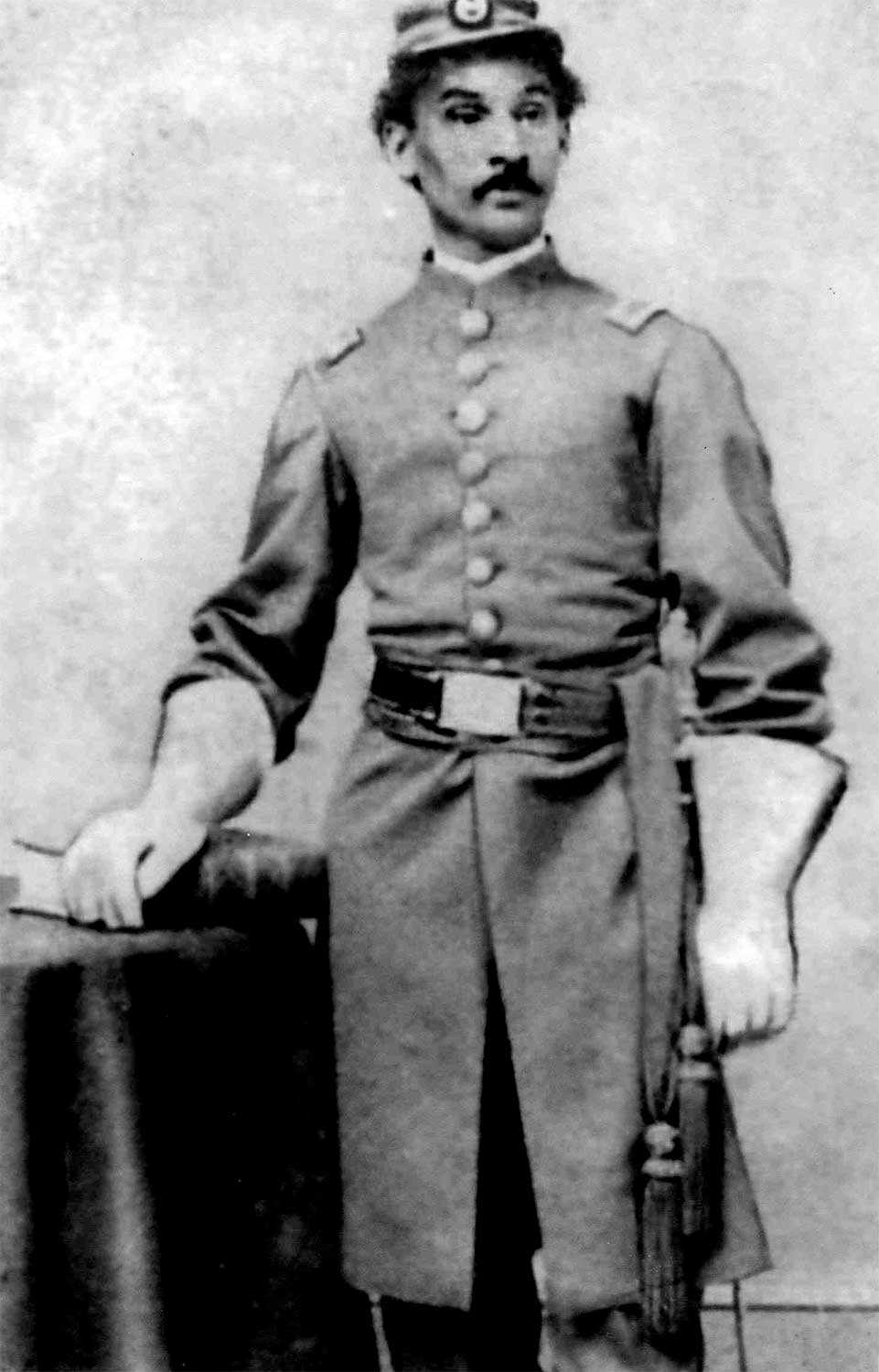

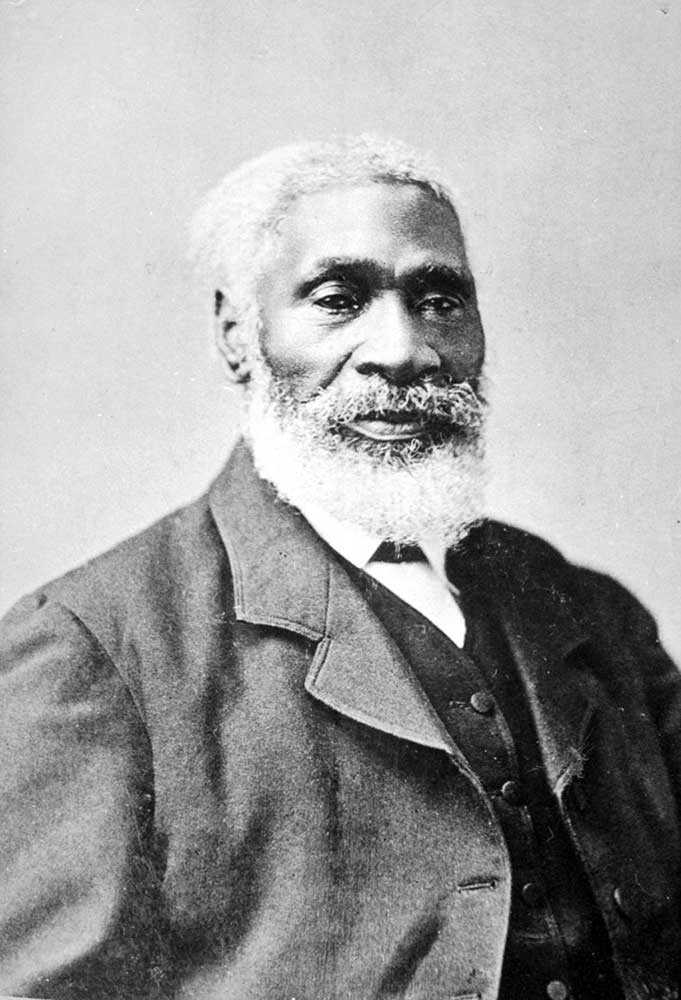

Together with community partners, the Provincial Plaque Program has helped, in recent years, to interpret a variety of voices from Ontario’s Black history. These include: the voice of Chloe Cooley – an enslaved woman whose cries, as she was violently forced into a boat on the Niagara River and sold to an American, so distressed some inhabitants of the province that Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe introduced the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada in 1793; the voice of Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott – the first Canadian-born doctor of African descent and a president of the Wilberforce Educational Institute; the voices of Hugh Burnett and the tireless campaigners of the National Unity Association; The Provincial Freeman newspaper and the many voices therein that championed social reform; and the collective voices of the early settlers of Black communities in Puce River, Queen’s Bush, Otterville and Hamilton.

The Provincial Plaque Program is uniquely positioned to respond to this shift identified in historiography. With more than 1,200 plaques throughout the province, the plaque program demonstrates that history is variegated. Plaques have proven to be a fitting medium through which to impart a diverse array of stories and experiences. Furthermore, the plaque program is self-consciously part of a process by which historical memory is invoked, and its success is achieved through partnerships and consultation.

Community partners, Trust staff and external researchers all contribute to the creation of each plaque. Yet those who read these plaques bring to them their own meanings, experiences and interpretations. Voices from the present and the past interact and the dialogue continues.

![F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/27790_boy_and_woman_520-web.jpg)