Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

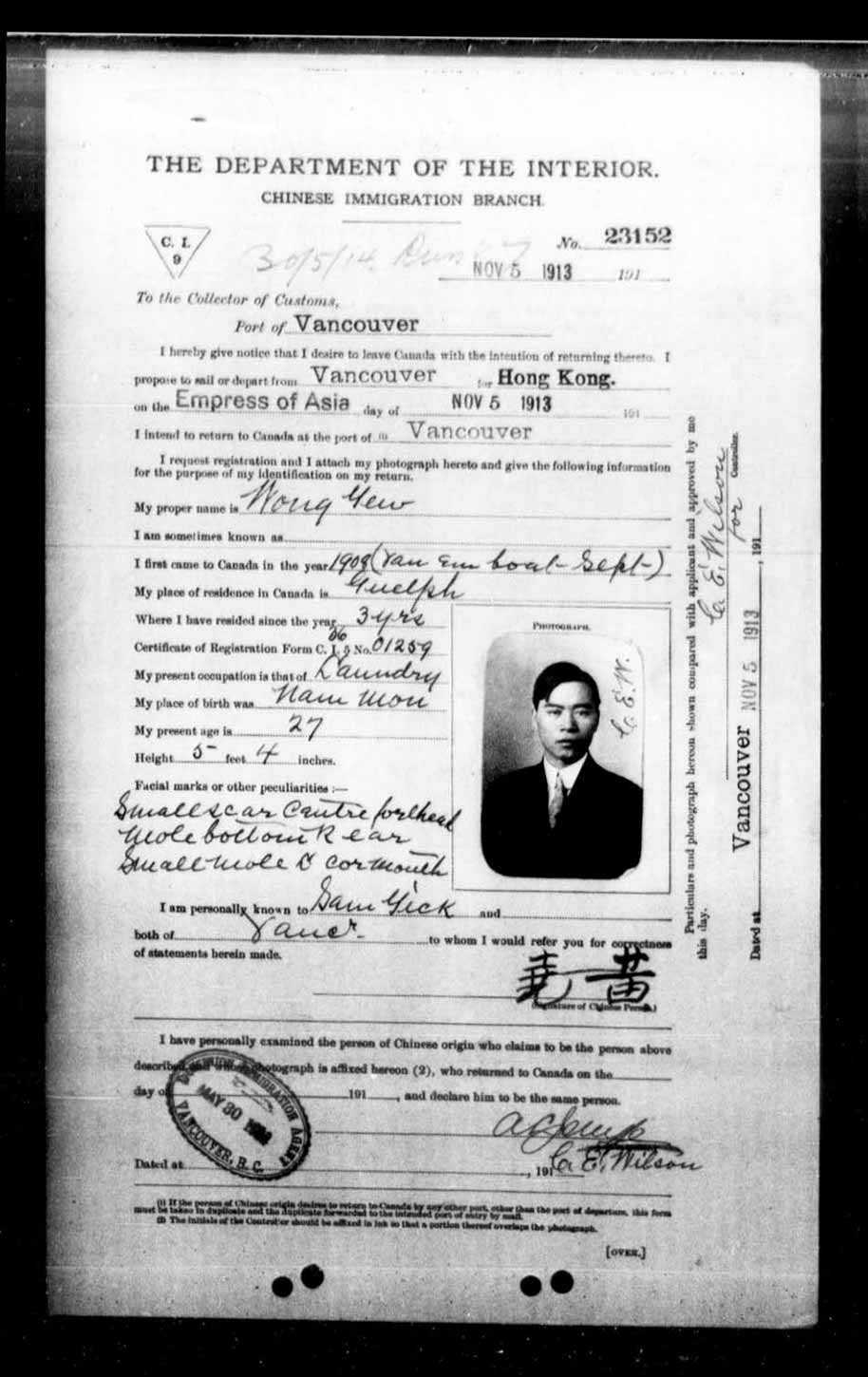

Chinese Immigration 9: Certificates that produced non-citizens

Between 1885 and 1923, Chinese immigrants to Canada were subjected to a “head tax,” according to the terms of the Chinese Immigration Act. This legislation generated a significant archive of materials now available to researchers through Library and Archives Canada (LAC). “Chinese Immigration 9” (C.I. 9) certificates are not well known but they should be. They are an incredibly rich resource for those who are interested in immigration history, genealogy and Chinese Canadian studies.

C.I. 9s were used to track Chinese immigrants who wished to leave Canada temporarily. These certificates were issued at ports of departure; copies of each certificate were kept on file by the federal government. Because of this system, we have a breathtakingly comprehensive archive of almost every Chinese man, woman and child who lived in Canada, and sought permission to travel, during this period. There are over 40,000 certificates held by LAC.

Starting in 1910, Chinese migrants had to attach an identification photograph to each certificate. This was the first widespread use of identification photography in Canada. My research focuses on exploring the identification photographs attached to each certificate and to thinking about how the certificates as a whole are documents that actively describe Chinese migrants as non-citizens. One of the premises of my research is that non-citizens are not simply there as refugees or temporary migrants. Rather, the state must produce non-citizens by actively documenting their exclusion precisely through elaborate apparatuses of surveillance, such as the C.I. 9 system.

In addition to an identification photograph, these certificates contain a substantial amount of information about each migrant – including name and age, year of arrival in Canada, name of the arrival vessel, profession in Canada, identifying marks, a signature in Chinese, English or, in some cases, a thumb print, and place of residence. The C.I. 9s were thus a kind of passport for non-citizens. These immigrants were not considered citizens, but they were given the right to return to Canada on the basis of this form. The C.I. 9s thus occupy a curious and richly ambiguous place as travel documents, which offer one of the rights of citizenship (the right of return) to non-citizens.

Notably, Chinese immigrants were not the only group of people whose mobility was surveilled during this period. For example, from 1885 until the mid-1930s, Indigenous people in Canada were subject to a pass system that attempted to track and restrict their movements. The pass system, however, was not nearly as successful or thorough as the head tax certificates for tracking and limiting mobility. It was not enacted in legislation and thus could not be enforced by the RCMP. It was still used to intimidate and discriminate against Indigenous peoples, but it was not explicitly a law.

By contrast, the Chinese head tax certificate system was definitively part of Canadian legislation through the Chinese Immigration Act (1885-1947). This legislation was amended in 1923 to exclude Chinese migrants from coming at all, but the C.I. 9s were still in force for those who remained. Until the repeal of the Chinese Immigration Act in 1947, Chinese migrants were explicitly denied access to citizenship. Chinese labour was central to national industries, such the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway, but Chinese immigrants were explicitly non-citizens.

Even though this is a difficult history, it has left a legacy of documents and images that are unparalleled. During the early 20th century, few people could afford photographic portraits. But because Canadian law demanded these portraits from Chinese migrants, and kept them on file, we now have a vast collection of tens of thousands of portraits of people who might otherwise never have been photographed. The vast majority of these certificates are for men. There are only a few hundred of women and children. This disparity tells us a great deal about the way in which the Chinese Immigration Act separated families and left most Chinese migrants alone without their loved ones.

Each certificate is the story of a life. Consider certificate number 23152 – for Wong Yew (shown opposite). Here, in 1913, he is 27 years old. He has been living in Guelph for three years, but had already been in Canada for two years before finding his way to Guelph. He works as a launderer. He has a small scar at the centre of his forehead, a mole at the bottom of his right ear, and small mole at the corner of his mouth. He has a friend who can vouch for his identity – Sam Yick, who lives in Vancouver. In this portrait, Yew is wearing a crisp white collar and looks directly at the camera in quiet dignity.

This is just one life out of many thousands that were tracked, captured and filed by the C.I. 9 system. I hope that by looking more closely at these documents, we can appreciate the stories of all of these lives and work to uncover the stories that they tell.