Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

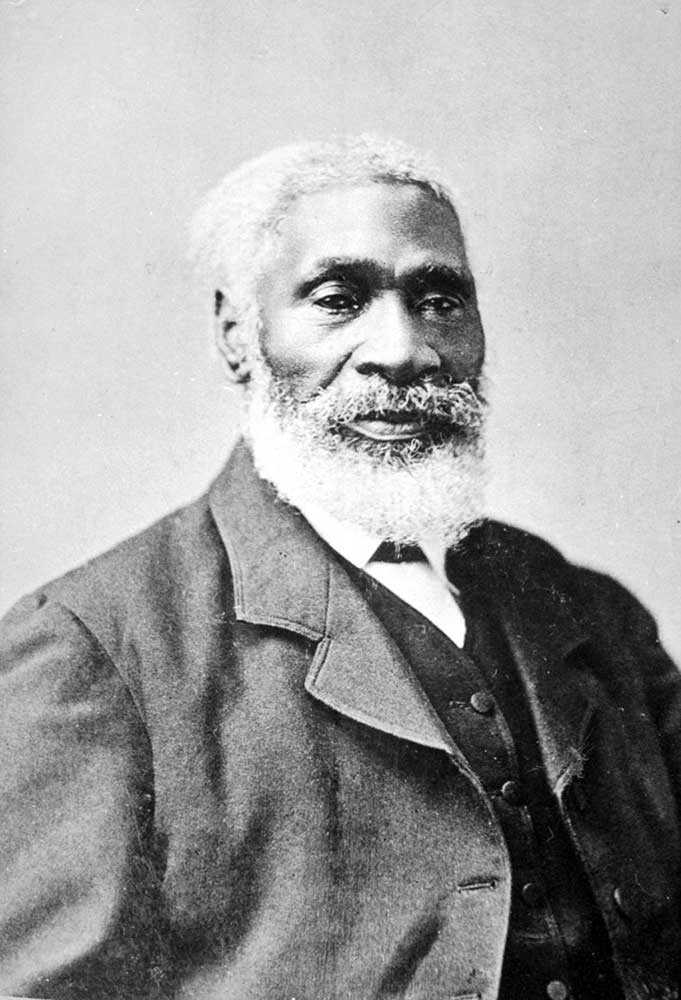

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Frost on the bedroom walls: Sharing women’s stories in public spaces

Expanding the narrative

Published Date: Sep 07, 2018

Photo: Women Are Persons! monument near the East Block on Parliament Hill, Ottawa. (Photo courtesy of Sean Marshall on Flickr.)

Historical narratives and symbols can be powerful tools that unify a nation. The stories we share about the past help shape our lives and make sense of our world. The recent debates over the removal of monuments or the renaming of public spaces reflects how stories can also be contentious. Public figures on display in parks can be reminders of a difficult past and thus act as a divisive rather than unifying memory. In Canada, such monuments have centred on male figures such as Sir John A. MacDonald, Governor Cornwallis of Halifax and Lord Stanley of Vancouver. Ongoing debates over who to commemorate, or not, are part of a broader discussion about who decides what stories Canadians celebrate and remember. New archival sources result in new interpretations and help shift the discussions, but many stories remain unknown. Traditional historical frameworks still drive the conversations and tend to frame issues of gender, race and class.

Missing from many of these discussions are the diverse stories of Canadian women, who have few public commemorations dedicated to them. According to historian Cecilia Morgan, for almost a century, between 1919 until 2008, Canadian women numbered only 6 per cent of public plaques or sites. Erected in 2000 on Parliament Hill, the “Women are Persons!” monument is one exception –and the product of decades of lobbying by women’s organizations. The absence of women from public stories and commemorative spaces gives us pause for thought, and begs the question: Why are so few Canadian women’s historical experiences well known?

Women, comprising half the population of Canada at any given time, are often absent from public stories. This led me to create a women’s history talk series in 2009 – HerstoriesCafe – to provide public space for honest examinations of women in the past. The talks showcase stories from women who share their personal history or their research work with the goal of creating a broader discussion about how women have influenced Canadian identity. HerstoriesCafe challenges the established masculine framework that distorts, or in some cases omits, women of the past and their accomplishments. We explore what we learn about women in museums, heritage sites and schools, and we learn about gender divisions and ideals that have been culturally determined and reinforced through national histories. HerstoriesCafe provides another lens – something that is critical to understanding the past in an equitable way. Talks take place in public spaces and each talk approaches a specific theme, including the arts, education and civic activism – focused on women’s historical experiences as well as links to today. Recent funding to update the website is in progress with intentions to network with teachers and students to bring women’s history into schools.

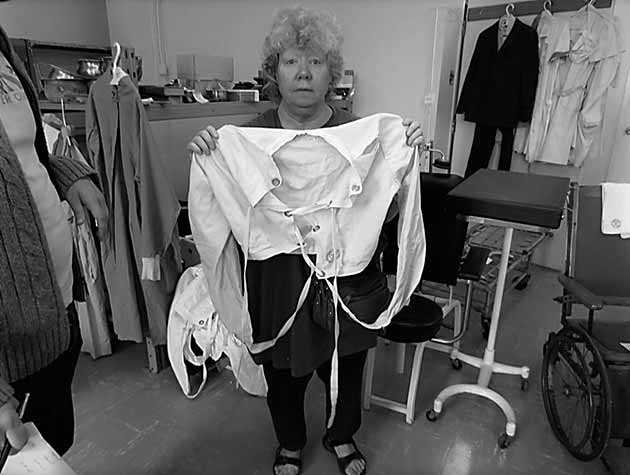

As an educator, I am aware that collective narratives are not only shared through heritage sites or public talks but also through history education. Even today, women are not construed as active historical subjects in multiple spaces in history classes. My research has explored why, and has traced the work of social movement activists, especially feminists, who identified with the “second wave” women’s movement to implement change. Aware that women remained isolated from the founding narratives and placed in supportive roles, reformers took action, working with publishers to produce a wide range of materials to alter the historical landscape. Despite their enormous efforts, only small steps have taken place. We have moved from inserting small icons of women on the side of history textbook pages to full-page discussions. The stories, however, remain adjunct to the dominant narrative and timelines, exploring “women’s roles” as a common form of analysis. For example, during the First World War, in addition to standard examinations about women’s factory labour, we might also explore how women activists like Julia Grace Wales and the International League of Peace and Freedom sought to bring the war to an end. Studying their work to stop the war allows students to explore civic activism. And we might ask, if we broadened the framework and placed women at the forefront of nation building, rather than as contributors, how would that alter our national stories? As President of the Ontario Heritage Fairs (https://www.ohhfa.ca), I am fascinated each year by students who focus on the historical experiences of women. Most recently, a project titled “The Bride’s Story” honoured five generations of Canadian women in one family. Another project, “Frost on the Bedroom Walls,” honoured a young girl’s grandmother and her experience in a Japanese internment camp in Canada during the Second World War. The projects allow us to hear women’s stories. The fairs, hosting over 25,000 students from over 20 school boards across the province, provide an important space for students to share their family, community and cultural heritage stories. Thanks to a recent government grant, we have expanded our work to incorporate digital projects, with the hope this will open up more opportunities for shared heritage stories.

The Ontario Women’s History Network (OWHN) provides another space for sharing women’s historical experiences. Founded in 1989, it remains active today, its annual conference a place to share the work of scholars, teachers and public historians. We explore women’s stories found in heritage documents, historical novels, diaries, committee meeting notes and travel books – leaders in charity organizations, community and child welfare associations, school boards, unions, women focused on social reform, juggling their family and work responsibilities. Recently, I had my university students examine women’s historical recipe books: a Cree recipe for pemmican, and early settler and modern recipes for biscuits and dried meat. The recipes speak to inter-relationships between people and the land, cultural heritage and the strategies women used in their daily lives.

As Canadians, we need to rethink definitions of historical significance. Once, public office or military achievement automatically led to public recognition. But now, people are considering the whole person. Life histories provide a broader examination of the record of a person’s life, emphasizing the experiences of the individual – a method that provides more space to explore women’s experiences. Individual women advocated for rights to property, labour, higher education and social and health issues. You can find some of these stories at the Canadian Committee on Women’s History (CCWH). Women’s activism within the various reform movements in Canada have impacted the kind of society we live in today and their activism is still evident in multiple places, including the Me Too movement.

Perhaps heritage communities, historians and history educators might jointly implement a plan to facilitate change. Recent steps across Canada to Indigenize institutions – a product of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada – has helped alter public narratives. This is important work, and links between institutions, heritage and Indigenous communities are stronger. We need to know more about the lives of Indigenous women.

Major changes to institutional systems are often viewed as “radical.” In terms of education, people tend to expect the same things that they experienced themselves. A full overhaul of existing structures is viewed as problematic; changing curriculum in incremental steps has always been the preferred model. As historical scholarship has demonstrated, however, we are in much need of broadening our focus on what counts as significant in Canadian history.

Let us create new timelines, remove labels that explore women’s narratives as “women’s issues,” and let us develop more partnerships between museums, heritage organizations, teachers and women’s groups. Let us actively support stronger partnerships between historical sites, archives and community groups, and engage in projects where women’s historical narratives are more accessible.