Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

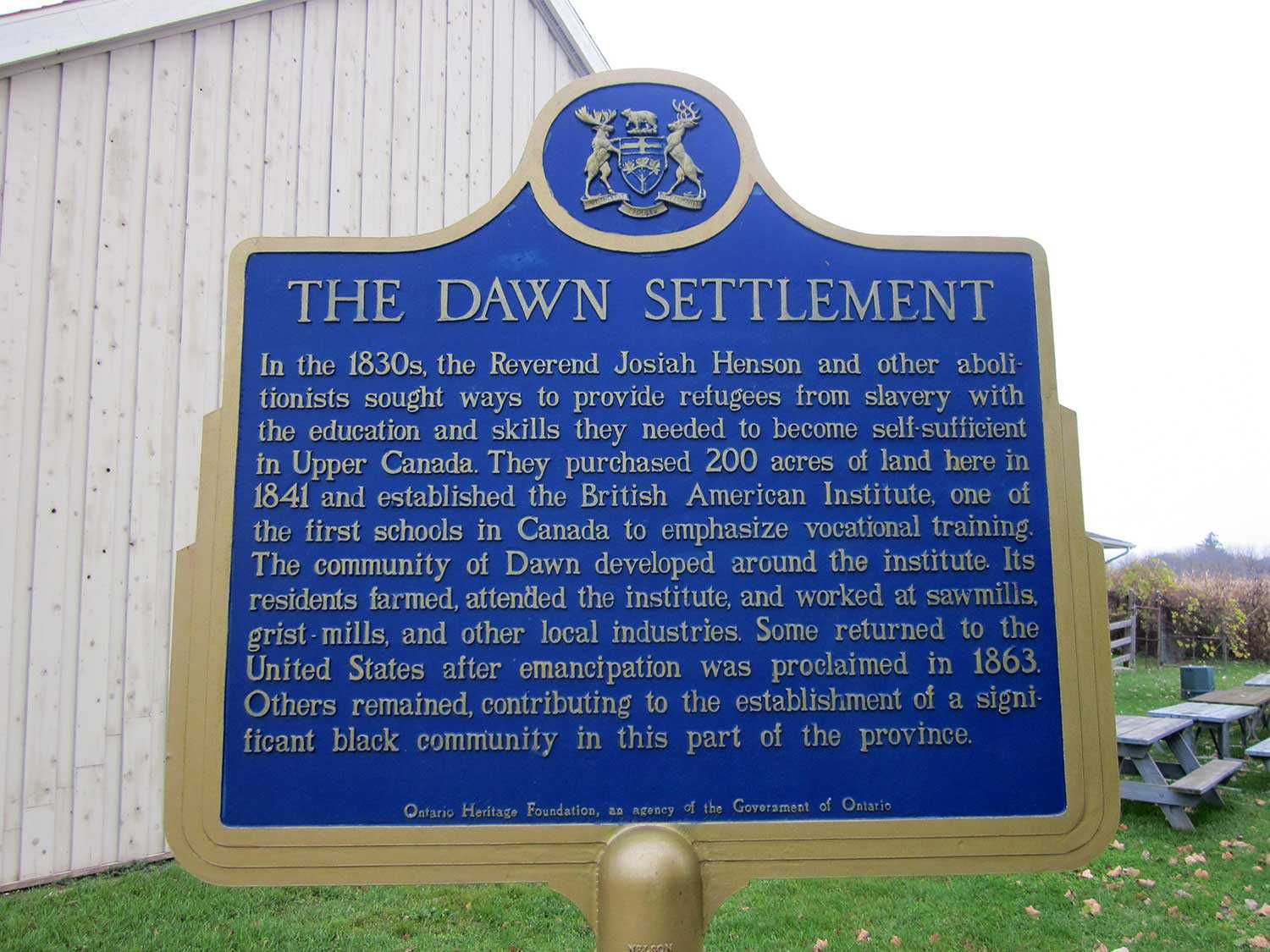

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Into the Kawarthas

Buildings and architecture, Community

Published Date: Jan 28, 2011

Photo: Peterborough Lift Lock National Historic Site of Canada © Ontario Tourism

When visitors first enter Peterborough’s stately city hall, they should look down. Inspired by the City Beautiful Movement – active in Canada from 1893 to 1930 – the exterior is designed so that passersby look up, towards the building’s stylized columns, clock tower and cupola. Once inside, however, looking down brings something unexpected into focus – a carefully crafted map of Peterborough County and the surrounding area.

The City of Peterborough is known as the gateway to the Kawarthas (a word derived from the Anishinaabe “land of reflections” or “shining waters”) and the impressive terrazzo floor offers a glimpse of the many rivers, lakes and communities that surround the city and comprise the county’s 3,800 square kilometres.

To the north of Peterborough County are dramatic outcroppings of the Precambrian rock punctuating a landscape of mixed pine, birch and maple forests – where the Kawartha Highlands Signature Site can be found. Expanded in 2003, this provincial preserve comprises almost 10 per cent of the county’s total area. Farther to the south, the expanse of Canadian Shield gives way to drumlins, moraines and eskers forged at the end of the last ice age and eventually rich, rolling agricultural plains that were once obscured at the bottom of prehistoric lakes. Peterborough County is at the heart of an ancient transport network of rivers and lakes and portages. Gradually expanded and connected through manmade canals in the 19th and early 20th centuries, this system became the Trent-Severn Waterway, a National Historic Site spanning 386 kilometres from Trenton on Lake Ontario to Port Severn on the shores of Georgian Bay.

In 1615, when Samuel de Champlain explored the region, he remarked on its attractiveness. The beauty of Peterborough County remains vital today as tourism continues to contribute to the region’s economy. Before the mid-20th century, proliferation of the automobile and steamers – such as the Lintonia and the Empress that plied the waters between Lakefield and Young’s Point – were common to the vacation experience in the county. Today, as 100 years ago, names such as Buckhorn, Burleigh Falls and Bobcaygeon inspire romantic visions of blue lakes, sunny days and long summer evenings at the cottage.

Long before the arrival of Champlain, this land of shining waters was home to countless generations of First Nations peoples who lived along its shores. In the northeast corner of Peterborough County, a vein of white marble juts from the granite. Petroglyphs carved into this stone depict both realistic and abstracted animal and human forms, and date to between AD 900 and 1400. The area of the petroglyphs, preserved as a provincial park, is a sacred space to the Anishinabek and is also commemorated as a National Historic Site for its lasting cultural significance.

In the southern portion of the county on the shores of Rice Lake, another important site of First Nations heritage can be found. Believed to be even older in origin than the petroglyphs, the nine burial mounds and surrounding area have provided archaeologists a unique glimpse at life in the region almost 2,000 years ago. The large serpentine mound is considered to be the only of one of its type in Canada. Of great spiritual value to the local Anishinabek people who care for the site, Serpent Mounds has also been recognized provincially and federally for its historical importance.

A third prehistoric site in the region is the Brock Street Burial found in downtown Peterborough. Believed to be on the crest of the traditional portage route between Chemong Lake and Little Lake, human remains and burial goods were found here in 1960 and again in 2005. All these sites attest to the long history of human habitation in the region, a fact that is celebrated every June with the Ode’min Giizis, or Strawberry Moon festival, which commemorates the Peterborough area as a traditional gathering place for the exchange of knowledge, ideas and friendship.

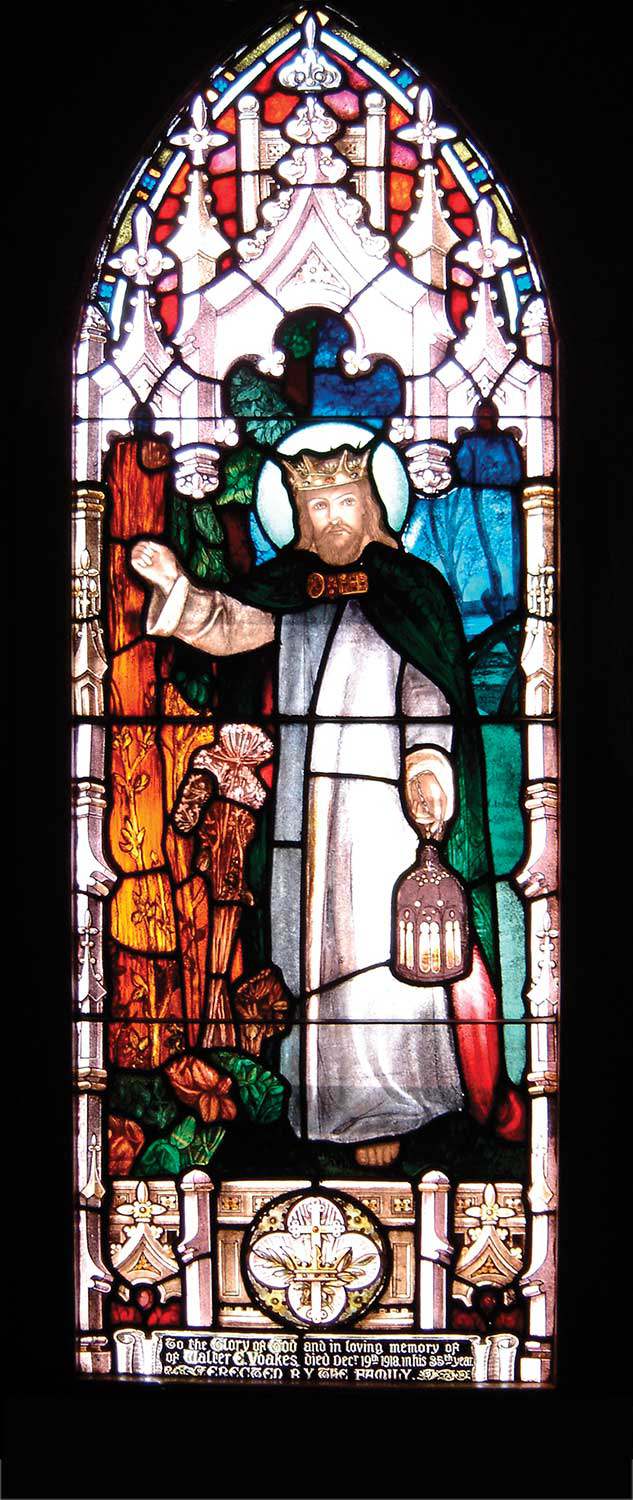

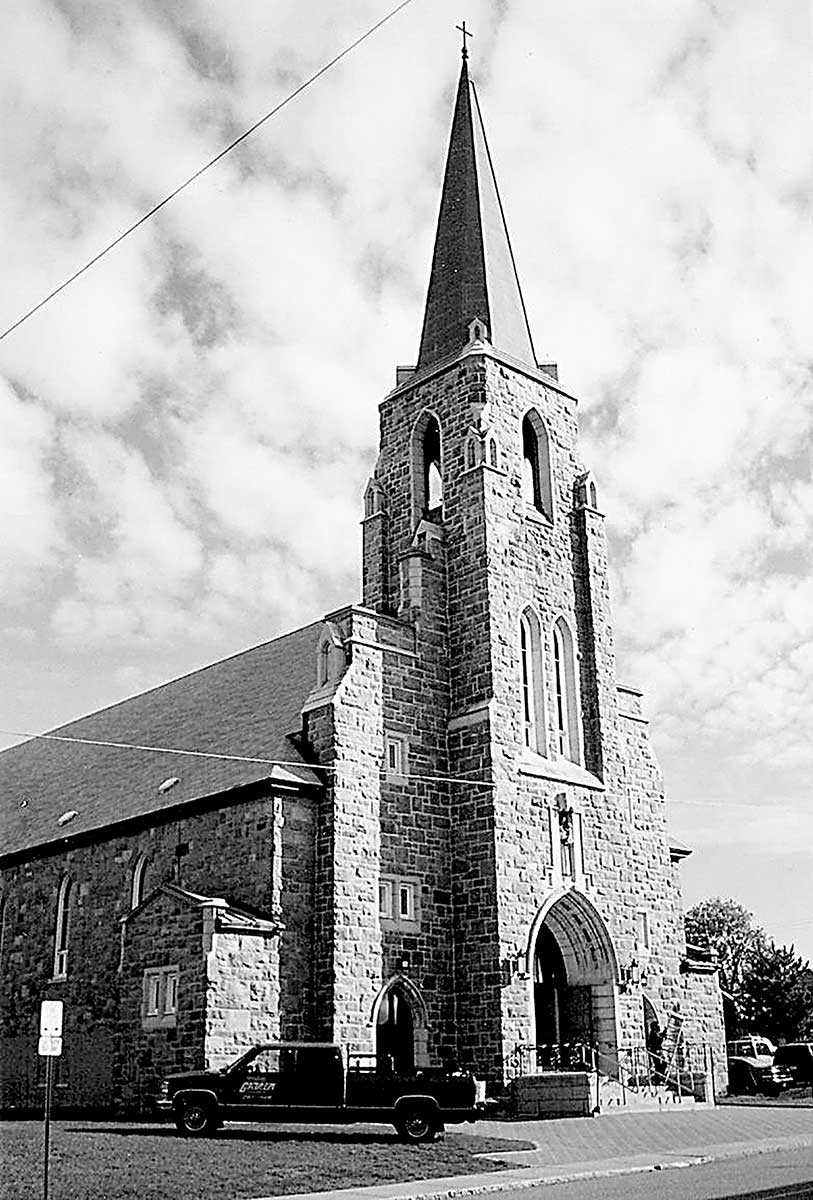

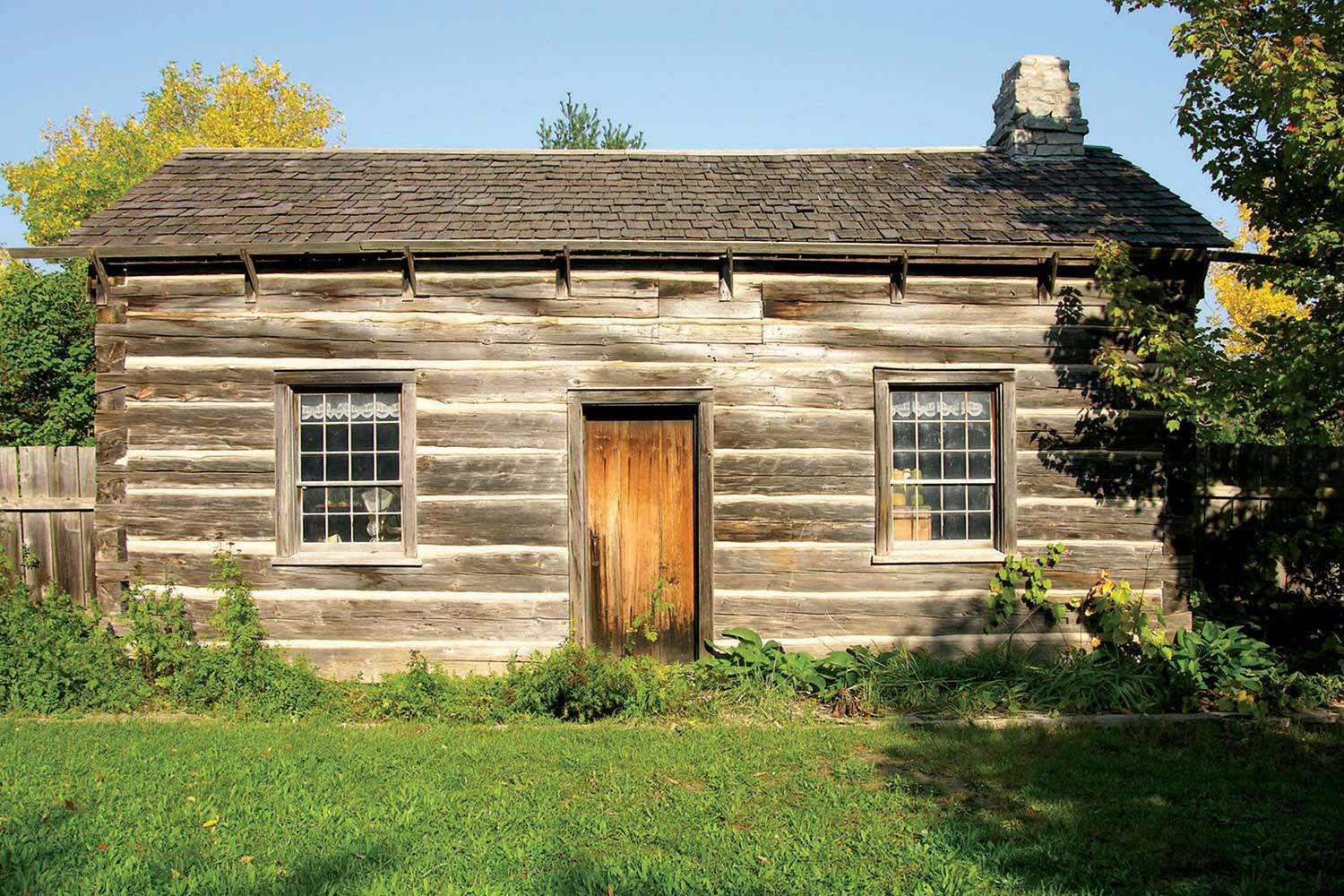

The first wave of European settlement to what was considered the “back townships” of the Newcastle District of Upper Canada began in 1818. Smith Township was initially surveyed and settled, soon followed by the townships of Otonabee and North Monaghan. Land and lumber proved to be the biggest draws to the region in the 19th century. In 1819, an Edinburgh-born miller named Adam Scott settled in a newly surveyed town and built a grist mill the following year. Initially known as Scott’s Plains, the settlement would later become known as Peterborough in honour of the local member of legislative council and commissioner of Crown Lands, Peter Robinson. In 1825, Robinson directed the immigration of 2,000 Irish settlers. This British government-sponsored endeavour provided a critical mass of farmers to bolster settlement and imprinted a distinctively Irish nature to the region, as well as a rich cultural heritage of dance, music and custom that is still celebrated in Peterborough today.

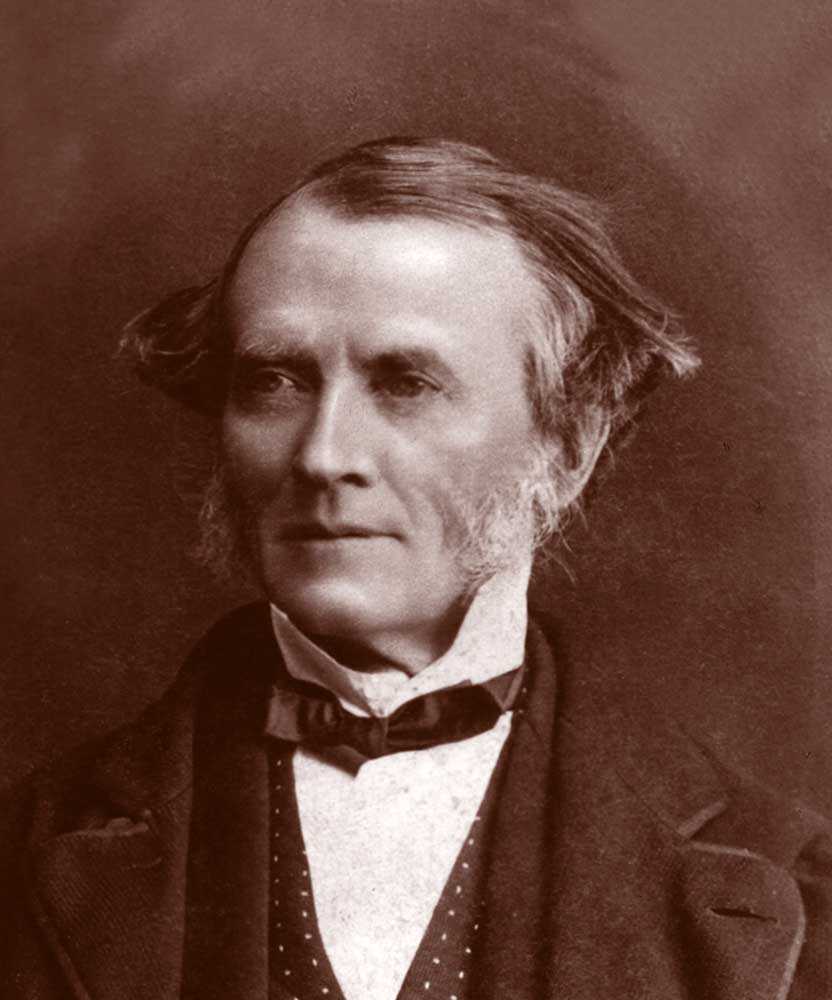

These early days of settlement in Peterborough County are well chronicled in diaries and published accounts of its inhabitants. Sisters Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill – accustomed to more refined English surroundings – wrote both of the rugged beauty and endless hardships of life in the bush, as did other early settlers such as Anne Langdon and Frances Stewart. These pioneer women, among others, offered early accounts of Canada as a wilderness, a metaphor that continues to resonate with Canadians and throughout the world. Early physician John Hutchison also knew well of the hardships of those early days of European settlement. His Peterborough home is preserved and operated by the Peterborough Historical Society as a testament to his pioneering efforts in medicine. It was also the Peterborough residence of his nephew Sir Sandford Fleming, who lived there before gaining worldwide recognition as an engineer and for his proposal of a system of Standard Time.

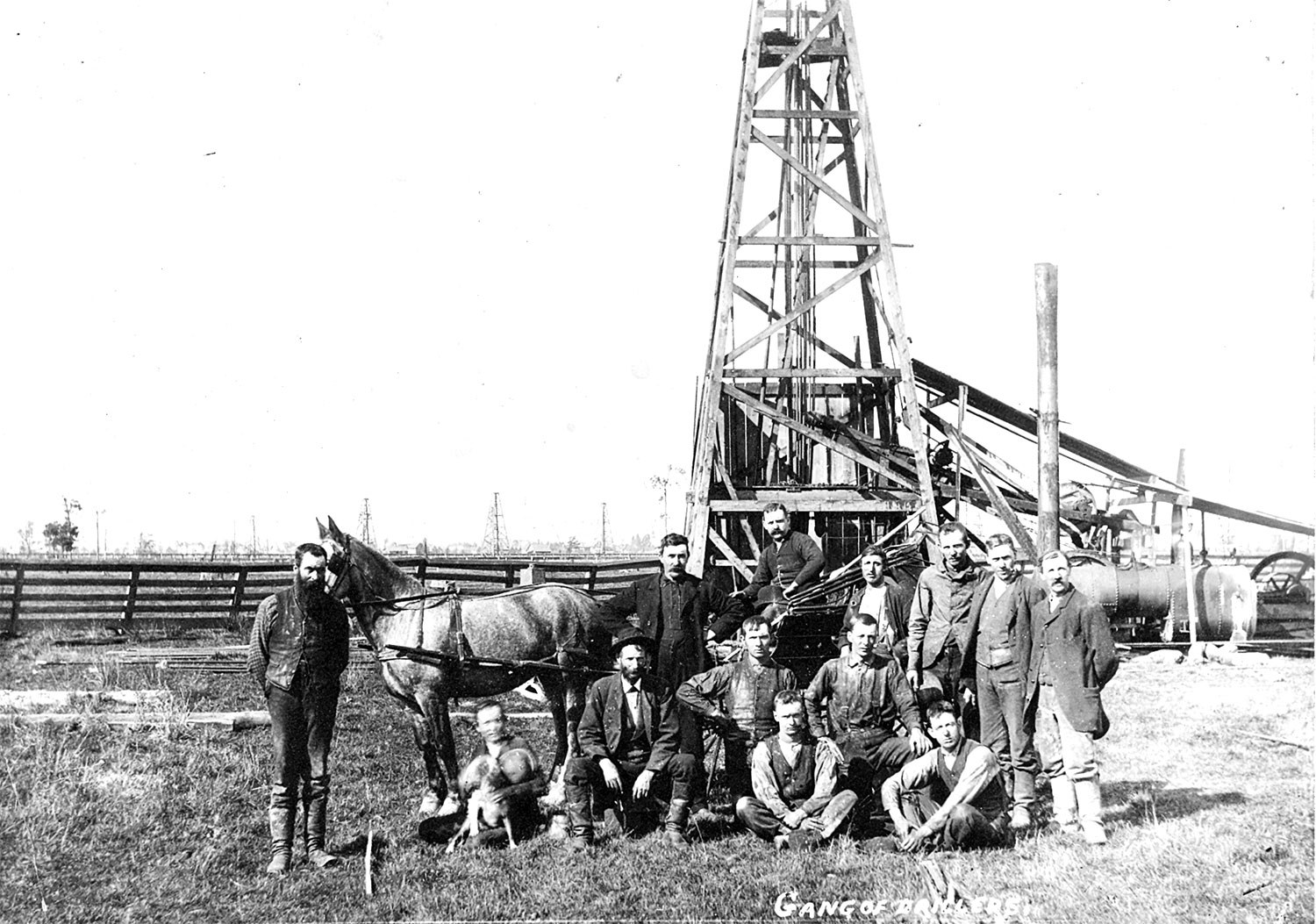

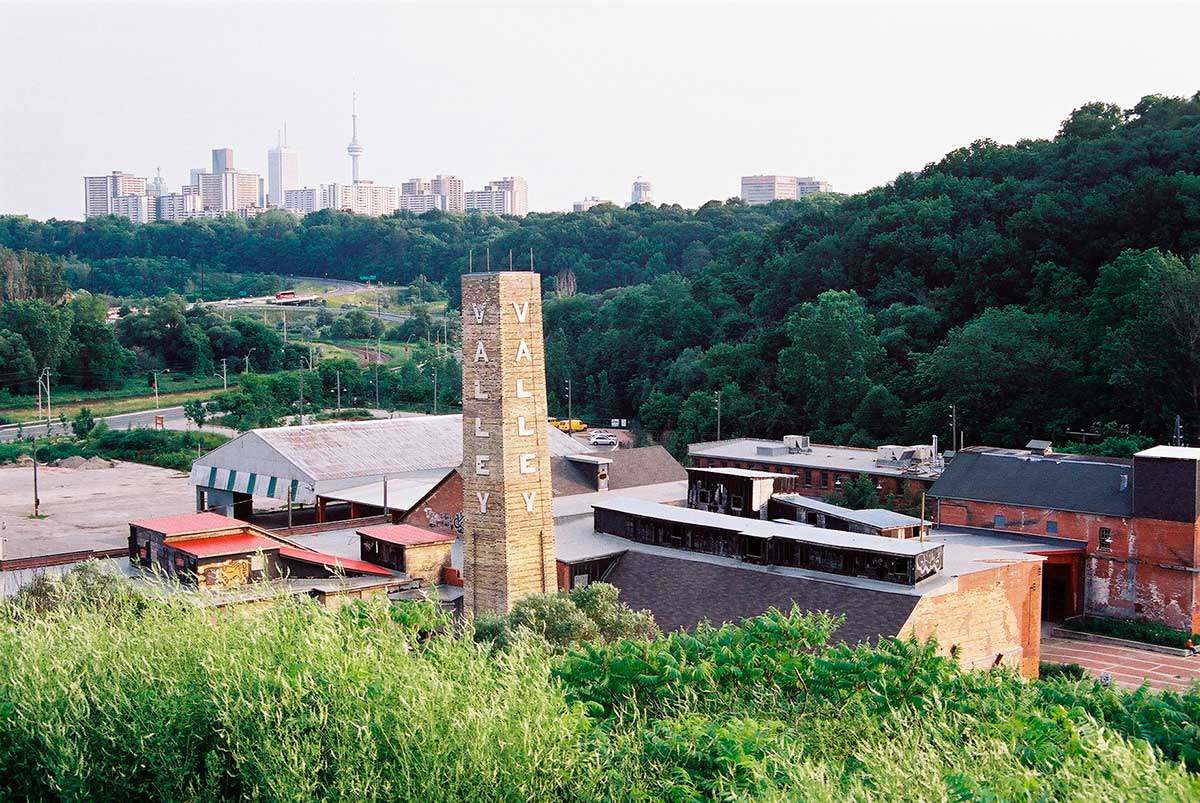

In addition to the land, early settlers were drawn to the region by its rich resources of timber and minerals. Peterborough County became synonymous with the production of lumber in the 19th century, fuelling the growth of the region as well as nearby settlements along Lake Ontario and Toronto. By the turn of the 20th century, the timber trade was eclipsed by other industry. Today, the spaces that were once occupied by lumber yards, timber sluices and log jams are now replaced by residential subdivisions, cottages and recreational boaters. Although not as famous as its timber industry, iron mining also factored in Peterborough County’s development. Traces of once-prosperous communities can still be seen today in ghost towns such as Blairton and Nephton, whose rise and eventual fall were inescapably linked to the minerals of the Canadian Shield.

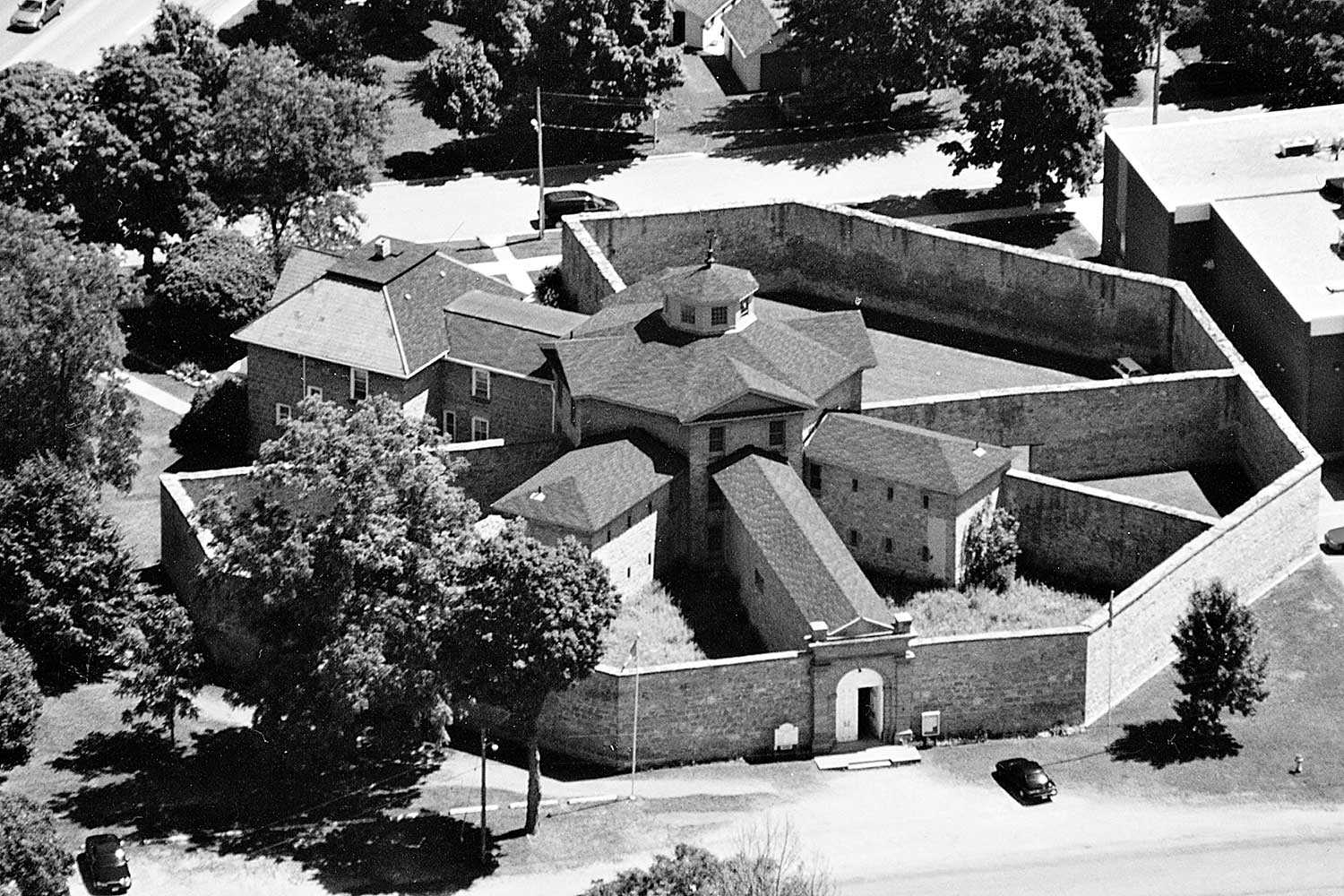

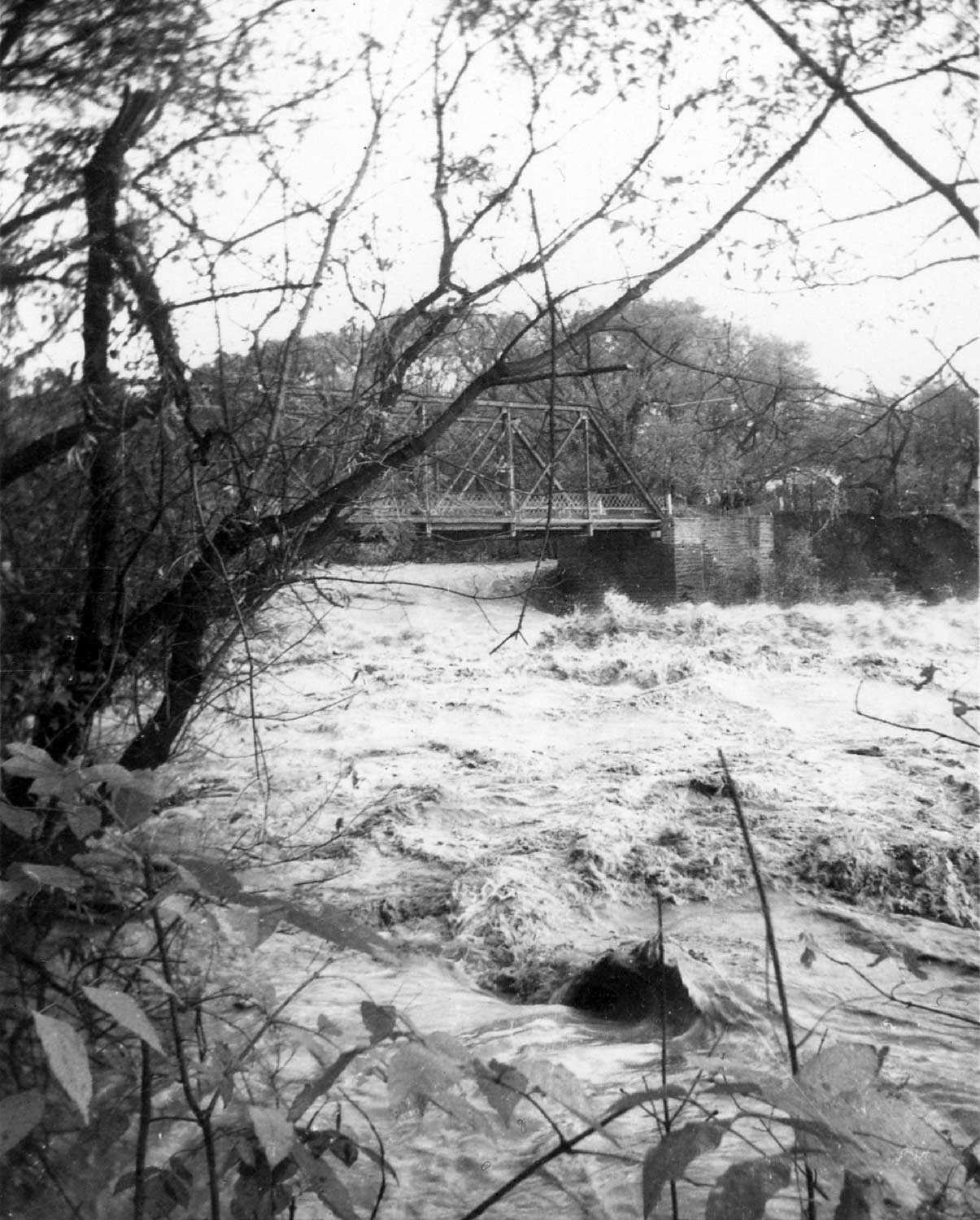

The Canadian Shield also offered the aggregate necessary to the production of concrete. The village of Lakefield became renowned for its production of the material, with the towering smokestack of one of its largest concrete factories being one of the final contemporary remnants of this once-lucrative trade. In 1904, Lock 21 – better known as the Peterborough Lift Lock – opened on the Trent Canal. One of the largest monolithic concrete structures in the world when poured, it continues to impress visitors and retains the title of the tallest hydraulic lift lock in the world. Over a drumlin known as Armour Hill and across the neighbourhood of East City is the Hunter Street Bridge. At the time of its construction in 1920, its 73.1-metre concrete span was the largest in Canada.

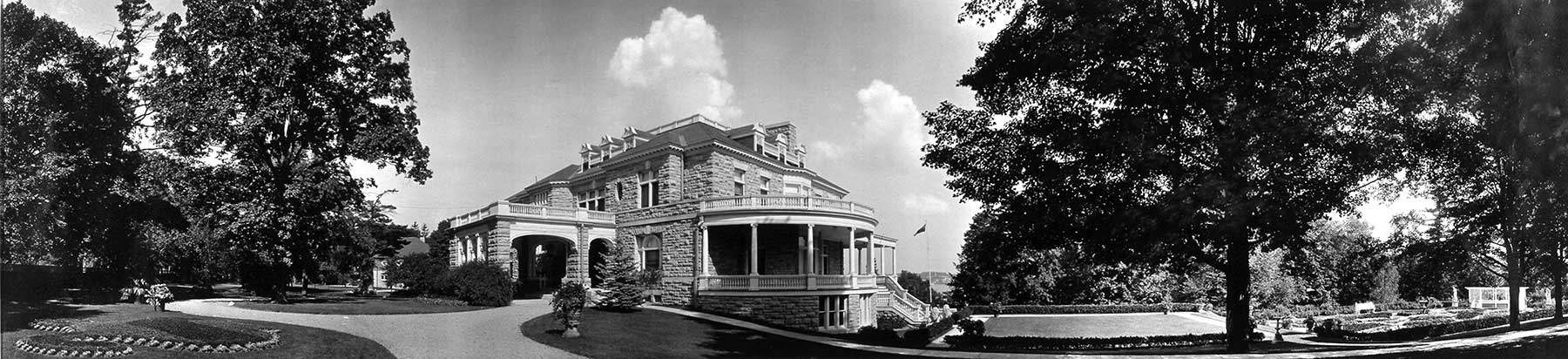

From the Hunter Street Bridge, the convergence of new and old in Peterborough can be most clearly seen. To the west is the bustling downtown that retains its historical character with its rows of late-19th-century commercial blocks, including the impressive Second Empire-inspired Morrow Building, built as a post office around 1878. Nearby is the city hall, flanked by several Romanesque Revival buildings, such as the Armouries, former YMCA and Peterborough Collegiate and Vocational School. At the centre of the adjacent Confederation Square is the war memorial, with bronze sculptures by Walter Seymour Allward, known for his design of Canada’s Vimy Memorial in France. Farther down George Street in the heart of the historic downtown is Market Hall, another impressive example of the city’s built heritage. Saved from demolition in the 1970s, it is now in the final stages of a multimillion dollar renovation that has restored its exterior façades, roof and distinctive clock tower.

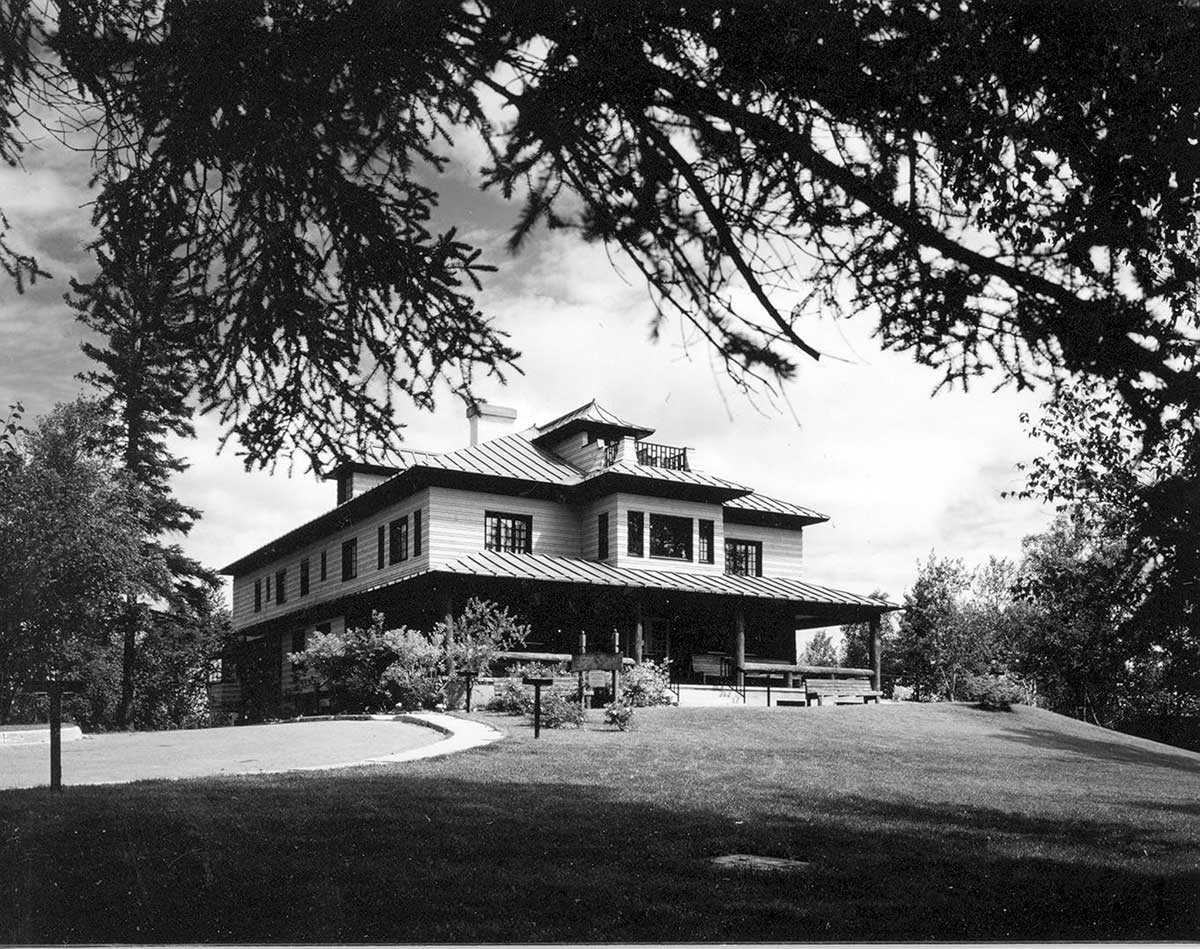

Flowing beneath the Hunter Street Bridge is the swift Otonabee River that led to Peterborough’s nickname as the “Electric City” in the early days of hydro generation. At the turn of the 20th century, many industries were attracted by the region’s accessible hydro as well as its water and rail transportation network – including Canadian General Electric, Quaker Oats, Westclox and Peterborough Canoe and Outboard Marine (now home to The Canadian Canoe Museum).

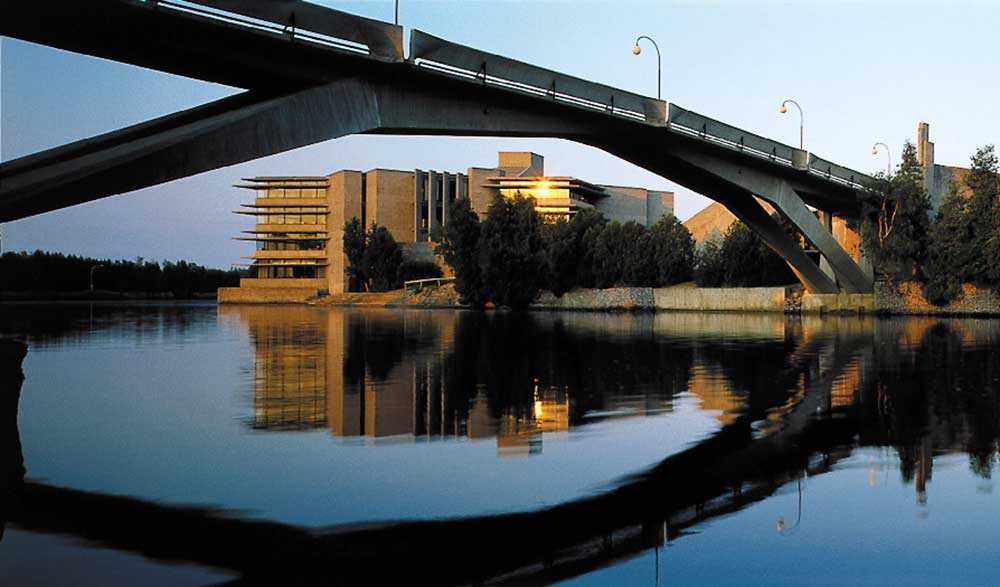

Trent University and Sir Sandford Fleming College, opened in 1964 and 1967 respectively, have attracted thousands of students to the region. In particular, Ron Thom’s central design for Trent University in concrete, rock and wood emulates Peterborough County’s rugged landscape and is a jewel of modern architecture on the Otonabee.

The dramatic mix of land, water, rock and forest has attracted, delighted, challenged and grounded the inhabitants of Peterborough County for millennia. In so doing, a rich historical legacy remains – a legacy that local heritage societies, museums, archives and concerned individuals remain ever vigilant in their work to preserve. From treetops to drumlins, from concrete bridges and locks to the shoreline, streets and even the floor of city hall, the natural beauty and cultural heritage of Peterborough County is everywhere one looks.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)