Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

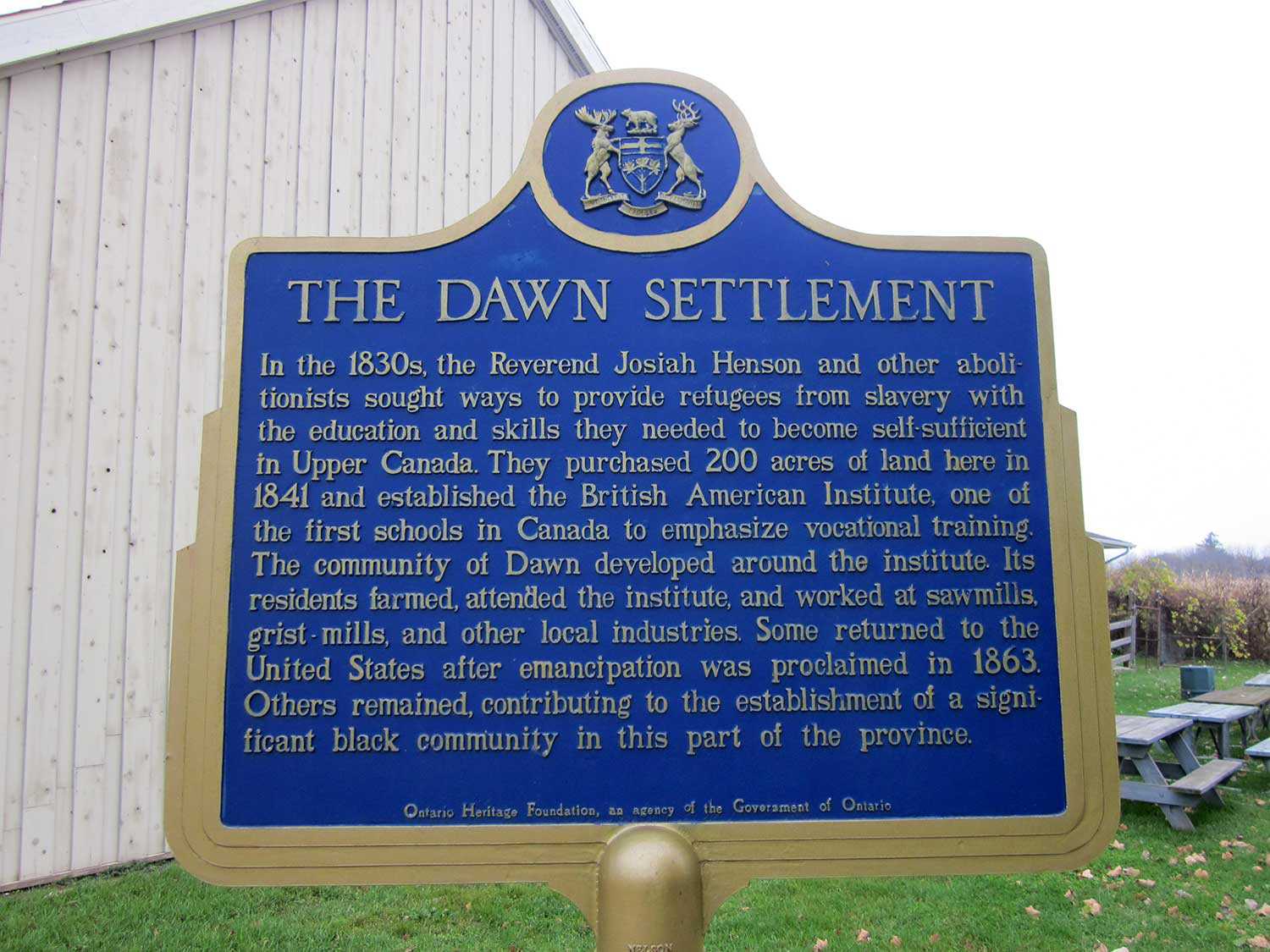

- Black heritage

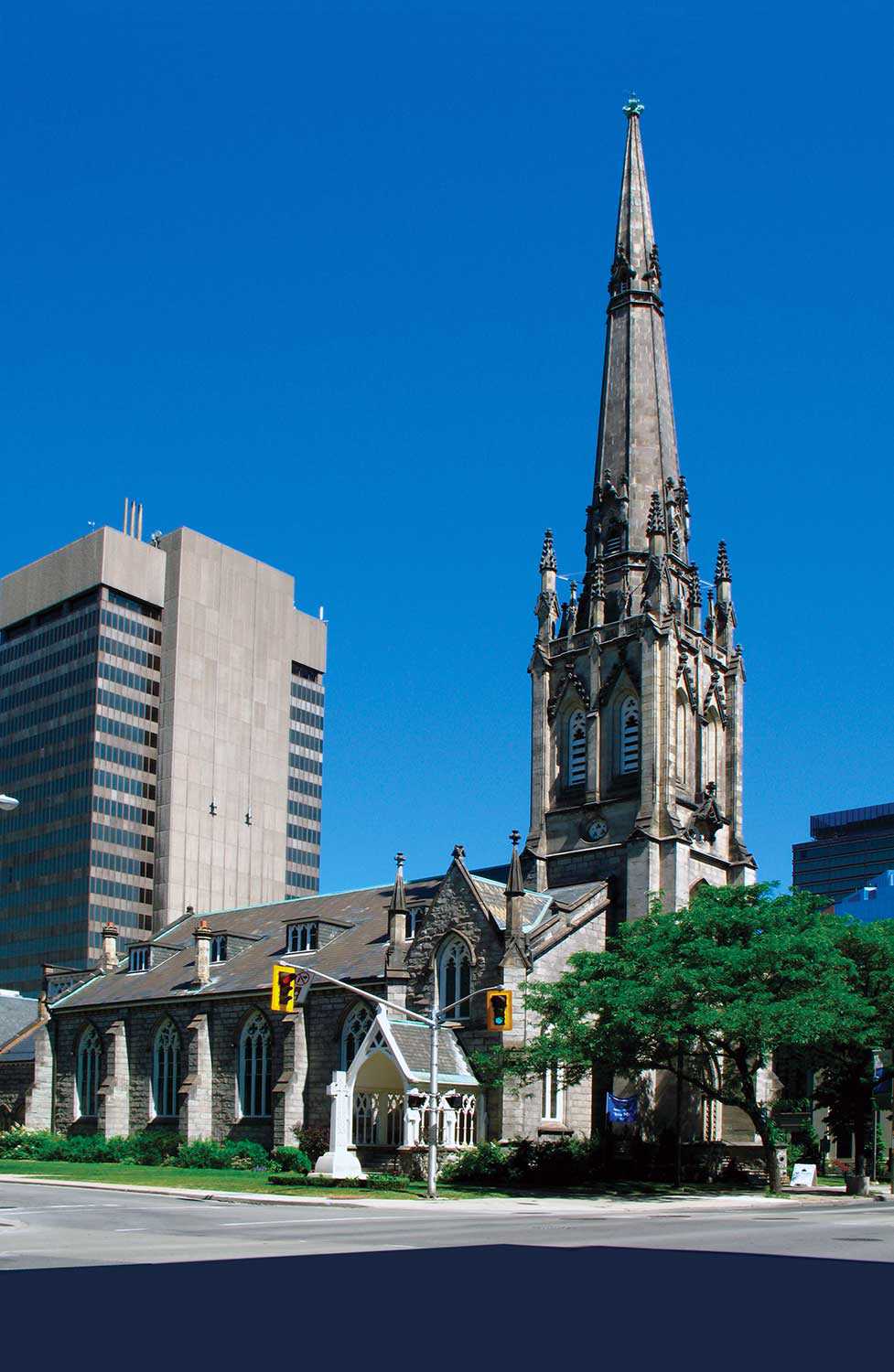

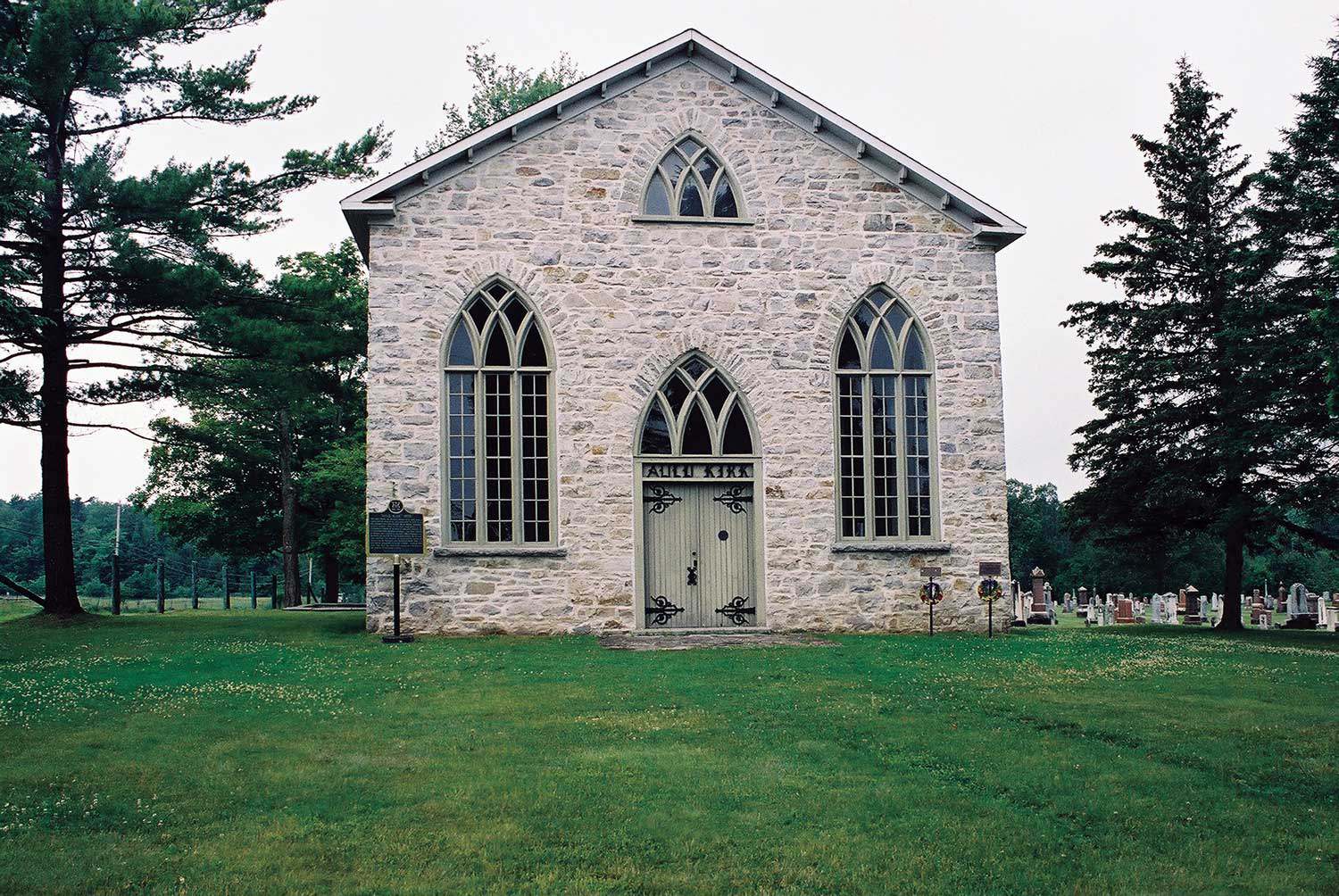

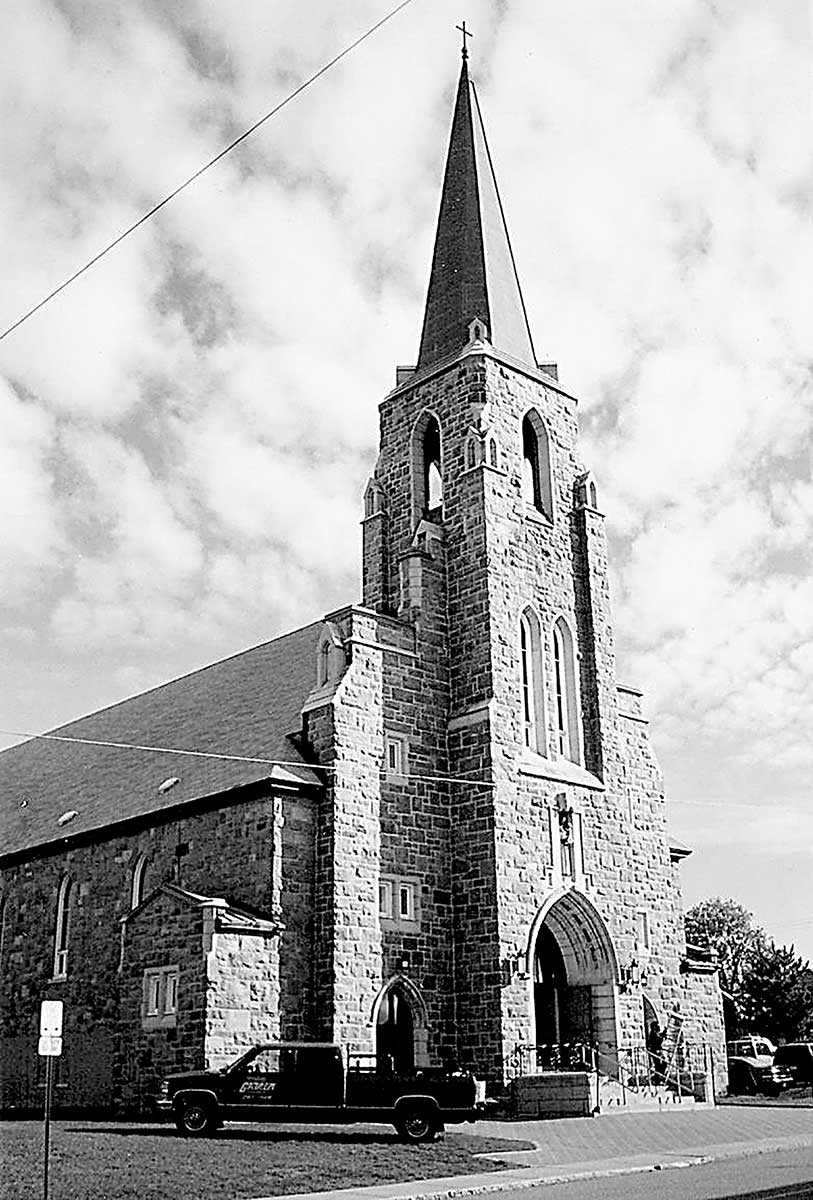

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

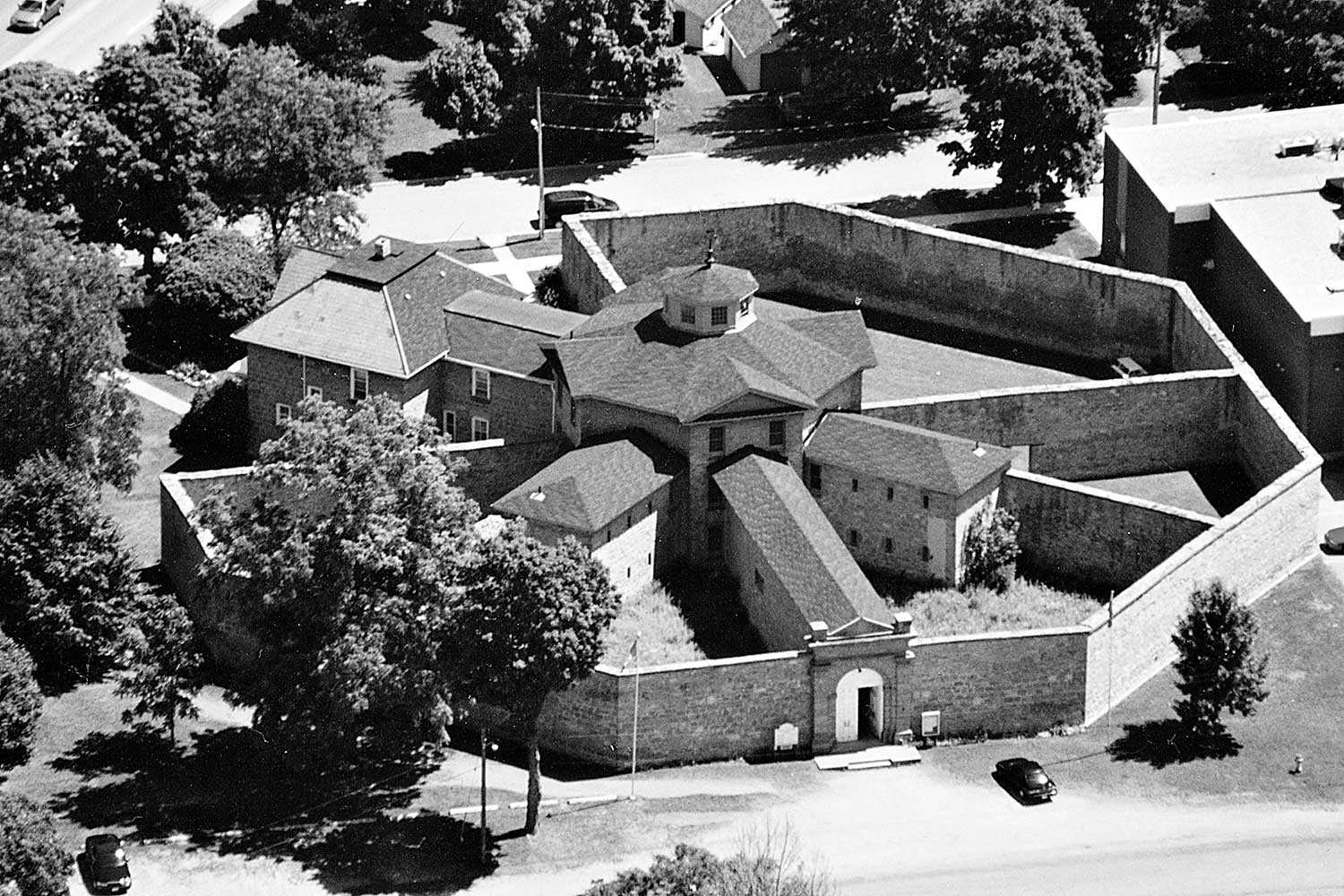

- Military heritage

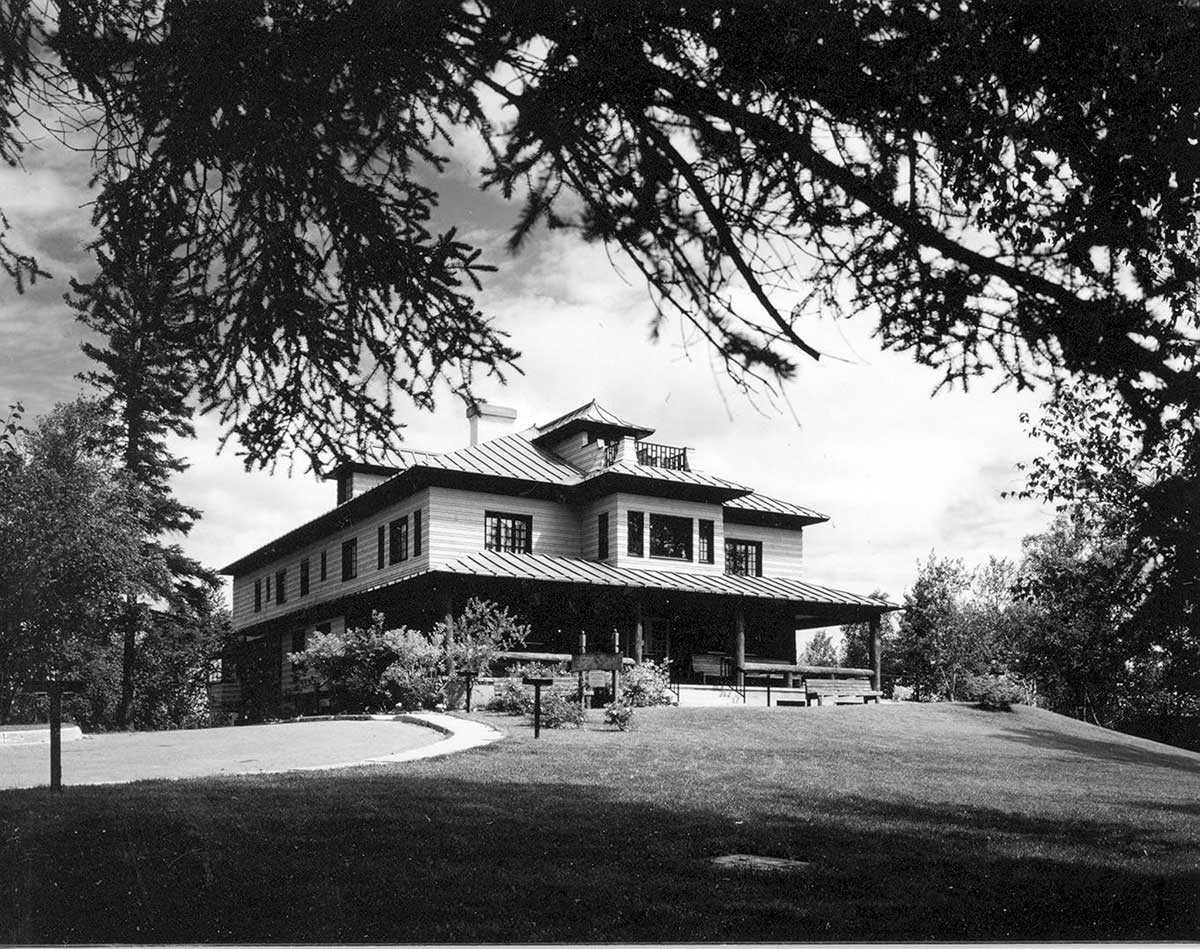

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

On the eve of war: Ontario in 1914

Military heritage, Community

Published Date: Feb 14, 2014

Photo: J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).

What was life like in Ontario during those years before the First World War? Before the war that saw men leave their families and friends to fight overseas – many of whom did not return, and those who did, returned as changed men? Before the war that made women persons and yet, at the same time, took away from many immigrants their most basic human rights? Before the war that defined a generation and helped shape the country’s emerging nationhood?

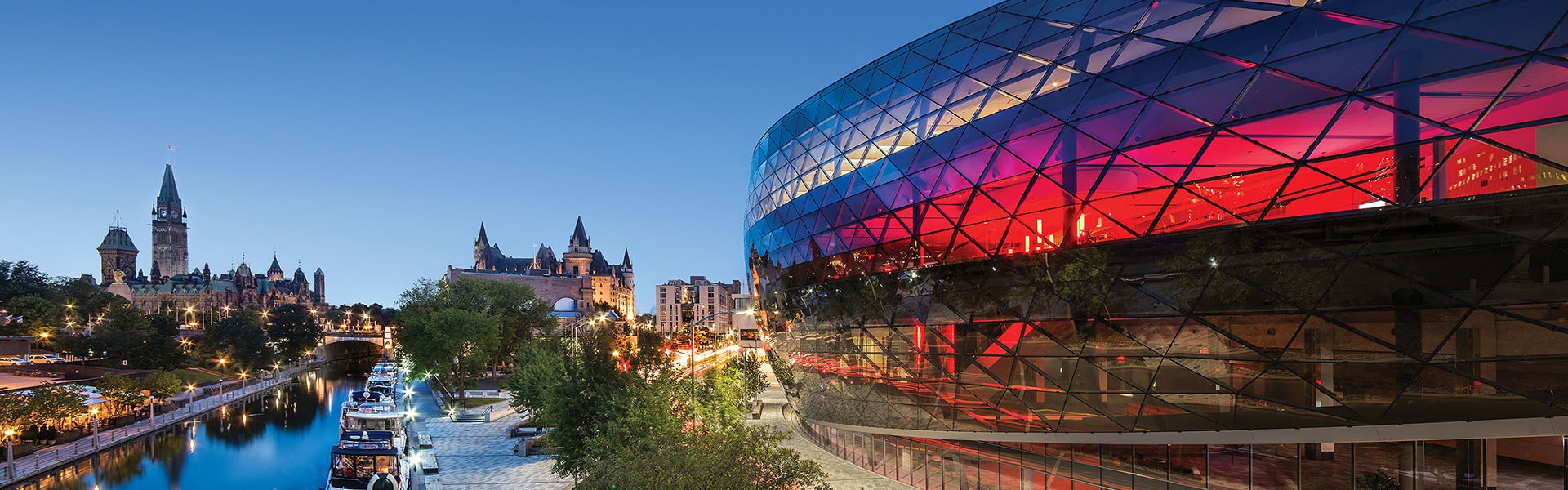

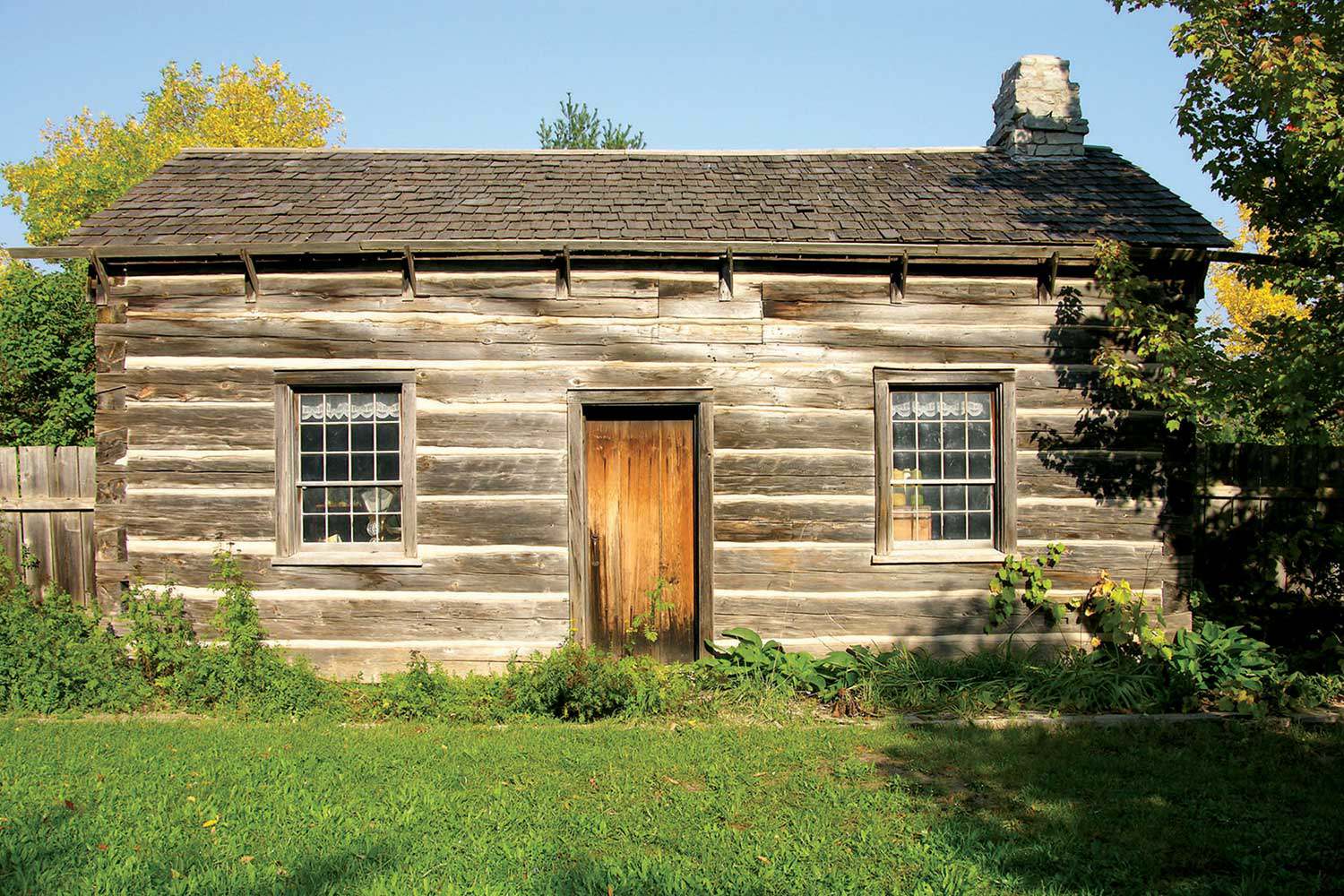

In 1914, Ontario was an economic power and political driver in Canada. The physical landscape of Ontario was divided into new and old – Old Ontario referring to areas of the province, predominantly in south-central Ontario, that had been settled in the 18th and 19th centuries, and New Ontario representing northern areas that were newly added to the province in 1912 and/or were opened for settlement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by railroads, shipping and homesteaders. This expansion created a network of communication and commercial activity linking old and new.

Immigration to Ontario came in waves from Britain, the United States, Europe and elsewhere. Communities of Italians and other non-British immigrants lived in Toronto, Germans in Berlin (renamed Kitchener during the war), French and Scandinavians in the north, while Aboriginal people largely lived on reserves. Yet, culturally, Ontario was predominantly British before the war, with 75 per cent of the population describing itself as being of British origin. Interestingly, 75 per cent of those people had, in fact, been born in Canada.

The Conservative premier of the day, James Pliny Whitney, although generally known for his forward-looking policies, was not as progressive in relation to language and religious tolerance. He proclaimed Ontario to be “an English province,” thereby alienating French-speaking Ontarians. Responding to school conditions in the Ottawa Valley and northeastern Ontario, Whitney introduced Regulation 17 in 1912, limiting the teaching of French in schools. Mounting protests forced the government to moderate its policy and, in 1927, bilingual schools were officially recognized.

Whitney was elected in 1905, after a generation of Liberal governments. He solidified the Conservative position among urban voters by establishing funding for the University of Toronto, freeing it from direct government control. He also established the Workmen’s Compensation Act in 1914 to provide for automatic compensation from the government to injured workers. After Whitney died in 1914, William Hearst served as premier for five years until being overturned by the United Farmers of Ontario.

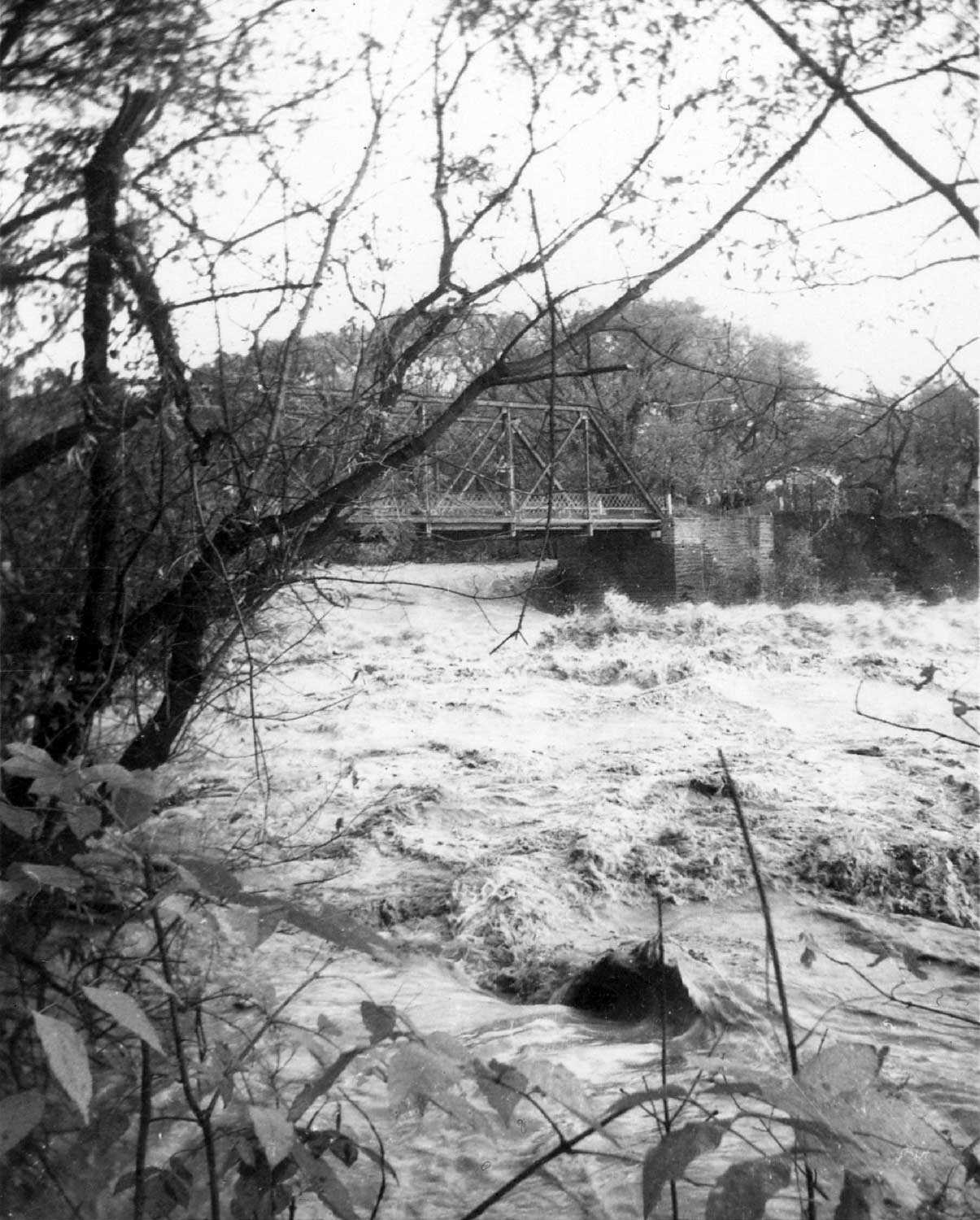

During this pre-war period, the control of utilities was a central political and economic issue in Ontario. Whitney worked to bring the control of gas, water and electric-light facilities out of municipal hands and under provincial control, creating Ontario Hydro in 1908. His move was intended to provide Ontario with cheap, state-controlled power that, in turn, would give business and industry in Ontario the opportunity to grow.

Technological change encouraged capital investment in Canada, driving the Ontario economy to new heights and diversity. But with private hydroelectric development in the North after the signing of Treaty Nine in 1905-06, came infringements on aboriginal rights.

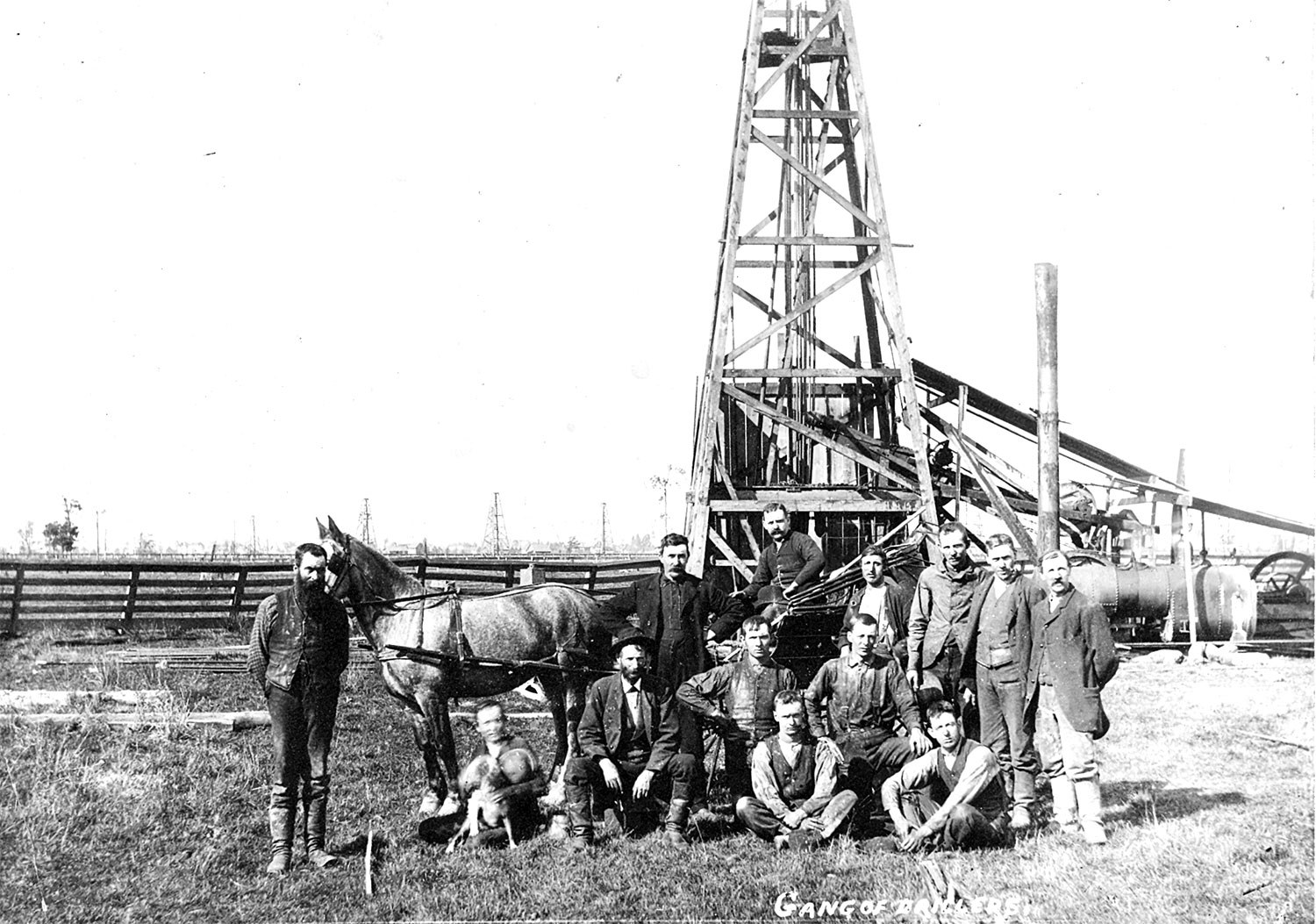

With Ontario’s economy booming before the First World War, traditional agricultural, forestry and primary manufacturing industries grew, giving rise to new industries in mining and secondary manufacturing, such as iron and steel industries. By 1911, these new industries employed more workers than any other sector in Ontario cities. Growth attracted people as well as capital, and immigration to Canada increased, especially in Ontario. Manufacturing output also significantly expanded, bringing migrants from rural areas to cities to find work. By 1914, most of the people in Ontario lived in cities, working in manufacturing jobs instead of farming and primary industries.

In 1913, a major depression in Ontario interrupted this boom. But the war overseas quickly primed the economy. Between 1916 and 1918, Canada saw over $1 billion in war material contracts, 60 per cent of which came from Ontario alone. Industrial production was concentrated in Toronto and south-central Ontario, drawing migrants from surrounding areas to work in those industries. The economy grew to include more lawyers, middle managers and clerks. Government expanded its reach, becoming more interventionist, especially as we have seen with regard to hydroelectric power. South-central Ontario became Ontario’s largest consumer market. Department stores appeared. And leisure activities grew. The number of nickelodeons, vaudeville theatres, saloons and dance halls in Toronto increased from five in 1900 to 112 by 1915.

Women faced discrimination in the workplace and society, being denied the most basic civil right of voting. The movement of young women from the country to cities presented, for many, a challenge to their accustomed rural life and social mores. At the time, domestic service was considered the proper employment for young women. Elsewhere, female workers were the last hired and first fired, and paid less than their male counterparts.

Women fought back against discrimination and expressed their identity in Ontario in several ways. The Women’s Institute, which grew to 900 branches by 1919, focused largely on providing women with social and community support within the context of improving home life. The suffrage movement grew to define and defend the rights of women. In the workplace, women fought against low wages, poor working conditions and long hours. In 1917, women were finally granted the right to vote, first exercising it in October 1919.

Following the rise of labour unions in late-19th-century Ontario, governments initiated efforts to establish a minimum standard of living – that is, to establish the budget needed to maintain the “health and decency” of a family of five. But the wages of most people fell short of this benchmark. Around the time of the war, the average adult male wages represented less than 75 per cent of the recommended amount.

With slow yet positive changes in the workforce, however, this new standard of living began to emerge. There was a gradual shift from lower-paying to higher-paying jobs. The number of working hours slowly declined, from 10 hours per day, six days per week, to nine hours per day with only a half day on Saturday. Companies also showed a rising awareness of the link between worker fatigue, workplace morale and productivity. The war also brought better safety measures and workplace conditions, such as improved ventilation, and – through wartime labour advocacy and reform – lunchrooms, midday meals at cost, pension plans and even company-sponsored sports teams.

Sadly, the state of public health in Ontario changed little from the 19th century through the first decade of the 20th. Slums expanded and infant mortality in 1909 rose to 180 per 1,000 live births – twice that of Rochester, New York, a comparably sized American city (and 37 times higher than in Ontario today). One of the major causes behind this shockingly high infant mortality rate was sewage. Toronto, for example, still dumped raw sewage into its harbour and pumped untreated water back into the city’s water system. In response, the city began to filter and chlorinate the water and introduce other measures that, by 1910, meant that Toronto sewage was no longer poisoning its drinking water.

During that time, too, increased focus was placed on other public health measures and preventative medicine. Specific concern was paid to the relationship between sanitation, milk and infant mortality. For example, inspectors began to test milk and dump whatever they found to be dirty. By 1913, Toronto required that milk had to be pasteurized. As a result, infant mortality fell significantly over the next five years. In 1912, Toronto also attempted to upgrade its housing stock, ordering slums to be condemned and attempting to eliminate outdoor privies, although indoor plumbing was costly and beyond the means of most workers.

Despite its challenges, Ontario did experience social reform. New religious reformers – the Social Gospel movement – argued that poverty, low wages, unemployment, overcrowded housing and poor public health in cities led to high mortality rates as well as disease. Social Gospel missions began offering services that later became the basis of the province’s social welfare system. New relief organizations were also formed, such as the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Christian Association, providing social recreation opportunities for youth, cheap meals for the poor, and classes teaching life and workplace skills. The Social Gospel movement also worked to eliminate public drunkenness, lower crime levels and generally improve social conditions among the poor. Members advocated moderation, then abstinence, then prohibition of alcohol. On the eve of the First World War, the issue of prohibition was a key part of the reform agenda and a central issue in provincial elections, resulting in the passing of the Temperance Act under Premier Hearst in 1916.

On the eve of war, Ontario was a province full of confidence and strength. For many, Ontario was a home that provided prosperity, stability and opportunity. But for others, it was not. Before the war, Ontario and its people faced and overcame many challenges that, in some ways, increasingly defined their understanding of themselves and their society. This was the social foundation for Ontario’s experience in the coming war that set the stage for changes that were to follow.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://questions-de-patrimoine.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)

![Rural values were an important factor in the 1914 provincial election. Threshing machine with steam engine [ca. 1914] (Archives of Ontario, C 224-0-0-34).](https://questions-de-patrimoine.ca/uploads/Articles/Kelly-threshing-machine-I0007460-web.jpg)

![The Ontario steel industry grew quickly during the pre-war years. Canadian Steel Foundries plant from across the Welland Canal [between 1913 and 1918] (Archives of Ontario, C 190-4-0-0-7).](https://questions-de-patrimoine.ca/uploads/Articles/Kelly-steel-foundries-I0020938-web.jpg)