Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

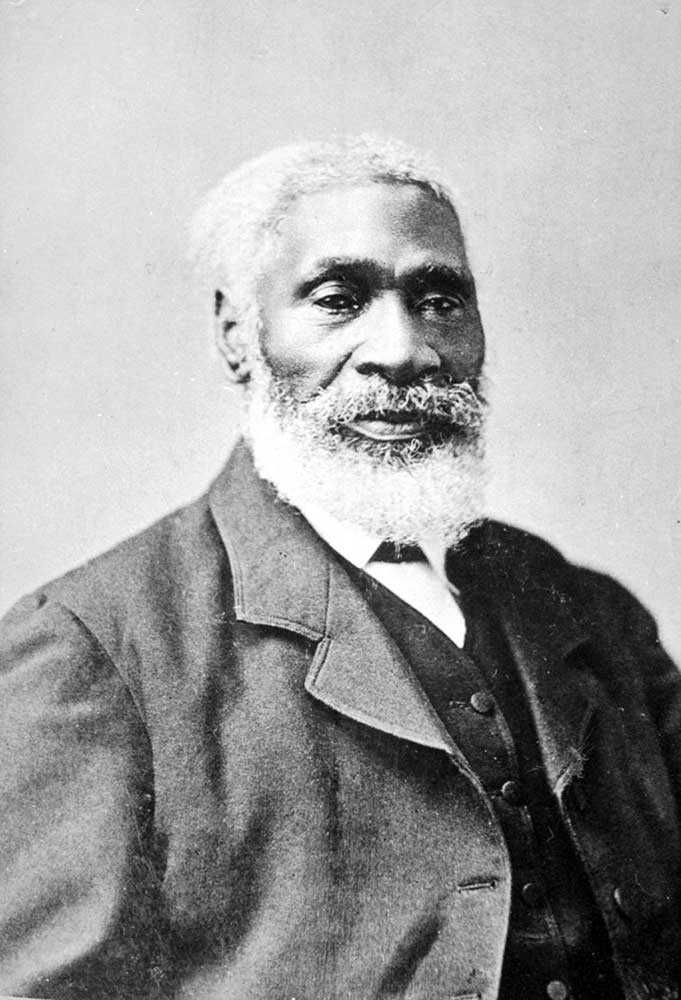

Portraits of a vanishing Canada

“The more you know about any life – or anything – the more you respect it.”

Louis Pfeifer was one of Kitchener-Waterloo’s last shoemakers. Between 2008 and 2018, Sunshine Chen and I talked with and photographed more than 50 people who were, like Louis, among the last of their kind in their trades, professions or other traditions. Most of these practices were once widespread, ingrained in the 20th-century experience.

“Fixing shoes is not so simple,” Louis added. “You have to know how to make them first, to see what’s involved, to see how things are put together.”

All of the people we interviewed were located in the cities and townships of Waterloo Region, but they represent a microcosm. Across North America, traditional manufacturing has been disrupted by global trade and automation, and storefront retail by changing consumer habits and sharply rising main-street rents. Working in the same profession, or for the same company, for one’s entire career is no longer the common thing that it was. Of course, every era brings changes. We’re told that change is the only constant – the idea has been around for centuries. Change turns us into philosophers, but one reason that we can reflect is because we adjust.

This philosophical impulse has generated a rich record of observations on change. Usually, we’re ambivalent. We feel pangs over what’s lost; we’re energized by what’s new. And time changes our perspective. In the 1800s, Paris changed profoundly as urban “renewal” cut and rebuilt swathes through the old city. At the time, the new streetscapes left many Parisians unimpressed. Today, they are beloved.

Whatever we feel about them, cultural changes inspire examination. We laud emerging methods and technologies. Eventually we consider what, and who, are becoming outmoded, but often only when they are nearly gone. And when a once-common thing is noticed because it’s disappearing, it’s a revelation. This can be a subtle and powerful experience – a shortcut to deep appreciation of our everyday world.

While change in general may be inevitable, the details never are. Specific changes happen for particular reasons. This is the stuff of our stories.

Asking people what they do, how they do it and how they feel about it, we heard about the skills, tools and processes of their work. We learned that old ways persist for all kinds of reasons.

We talked with people like Louis, who kept going not because he was a holdout, but because we are. People still want shoes fixed. Louis’s skills, based on his knowledge of shoe “anatomy,” became a rare specialty, in demand even as shoemakers disappeared.

We talked with people like Dan Bergeron, among the last sign painters, who persisted partly because he loved his tools and materials – feeling the enamel flow from his brush, choosing the right brush for the job. So, when vinyl lettering became the trade standard, Dan kept painting. He tried vinyl at first, but said, “It took all the fun out of my work. I just sat there and listened to the machine cut out my letters.”

We talked with people like Ludovika Berta who persisted partly for the connection with satisfied customers, or the connection with their own roots, and the fulfillment they drew from both. Ludovika, one of a dwindling number of furriers in a fading trade, said, “My father was in the fur business ... I started in Europe when I was fifteen years old. I saw what my father is doing, how he is doing it. I watched him.” She said her father was proud of her, especially because “The female job is always finishing ... but I learned every year a little bit, slowly ... blocking, sewing, I cut the fur, everything.”

But what do the rest of us gain from this newfound knowledge? I think it’s more than can be explained by aphorisms like the one about us needing to know where we’ve been in order to know where we’re going, just as “change is the only constant” falls short of recognizing the other constant in that observation: that we observe and seek to know the stories of others, and doing so, come to better know ourselves.

Our project will be published this fall as the book Overtime: Portraits of a Vanishing Canada, by Ontario’s award-winning artisanal publisher The Porcupine’s Quill. [Photos courtesy of Karl Kessler]