Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

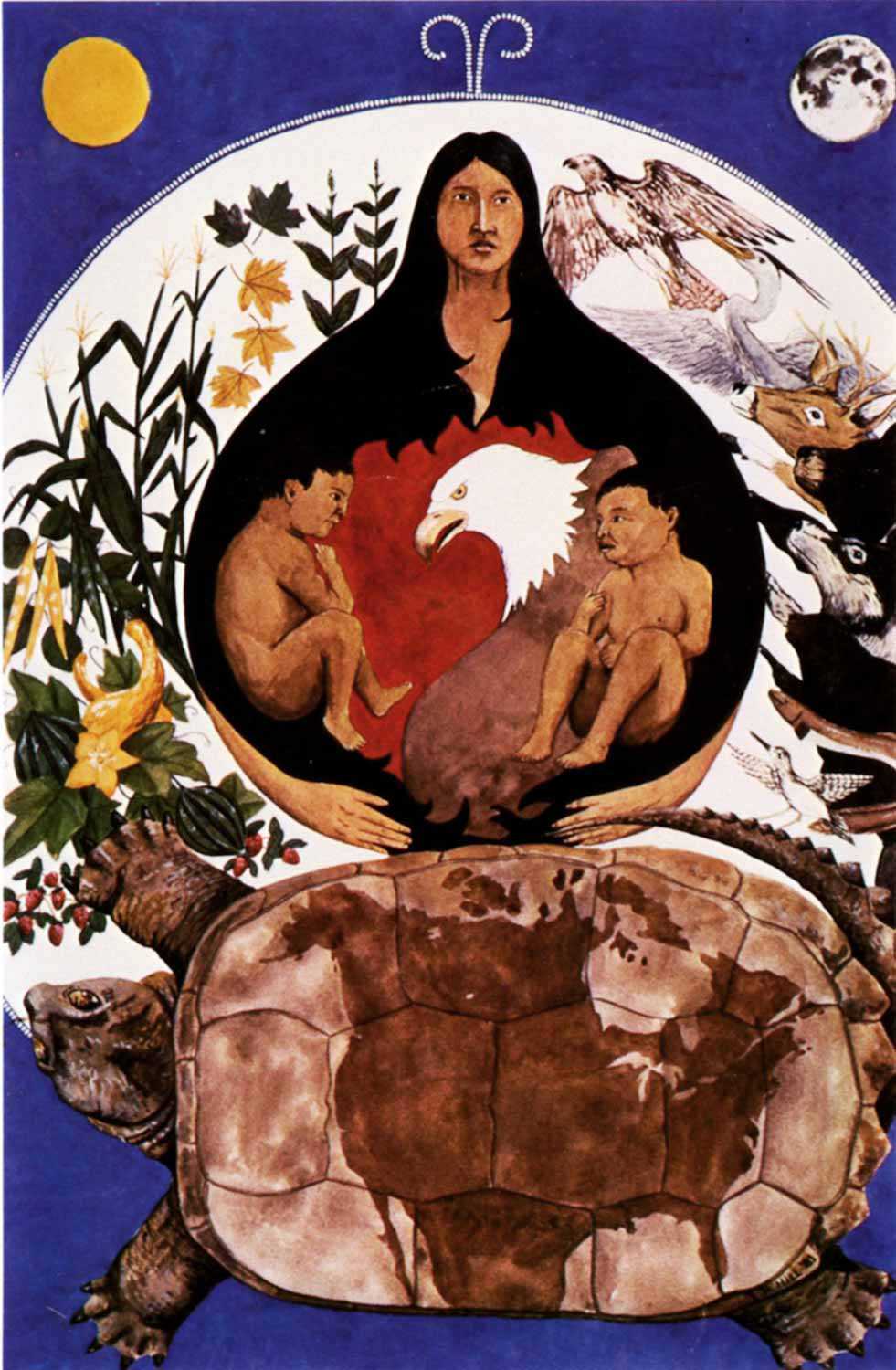

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

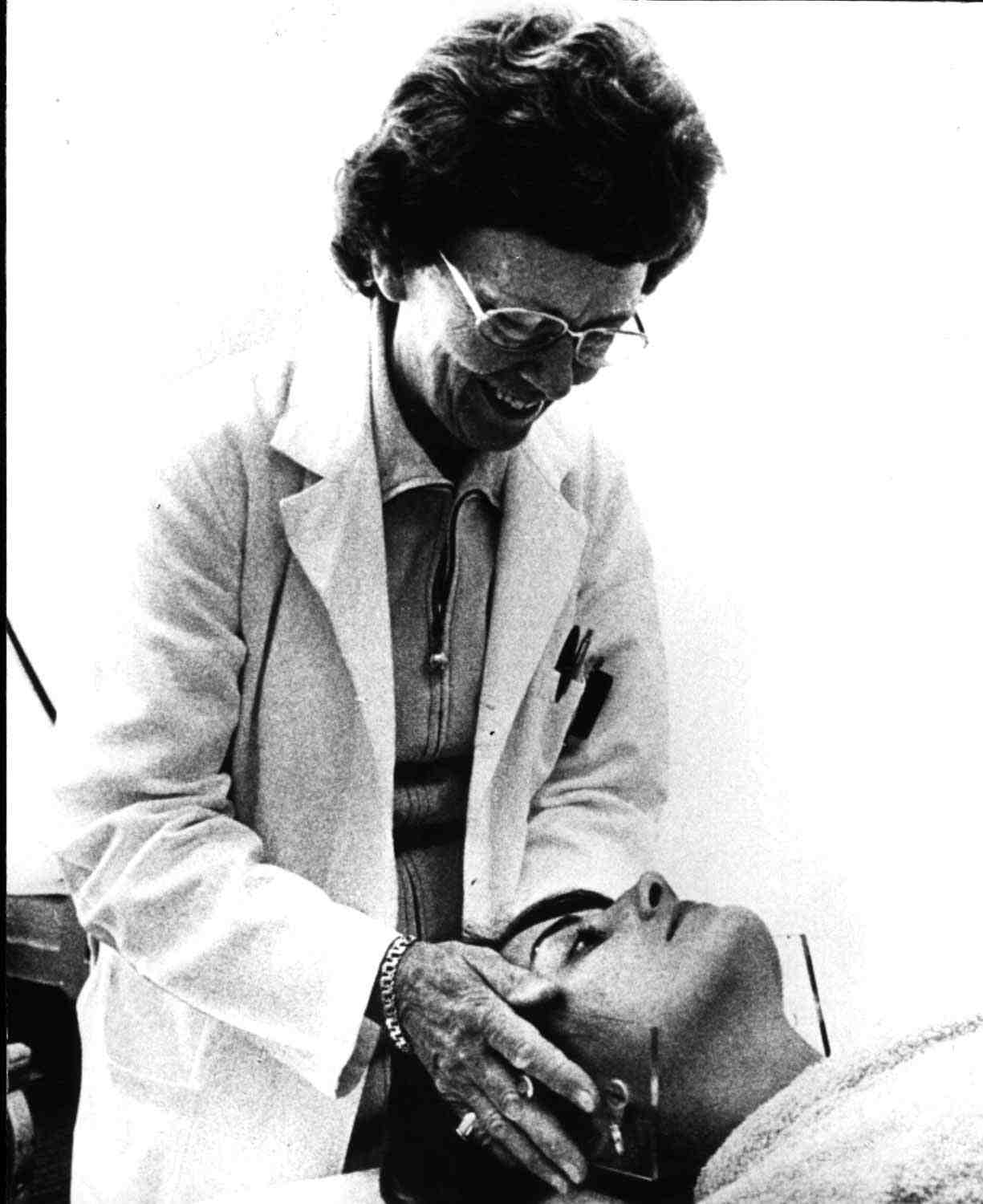

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

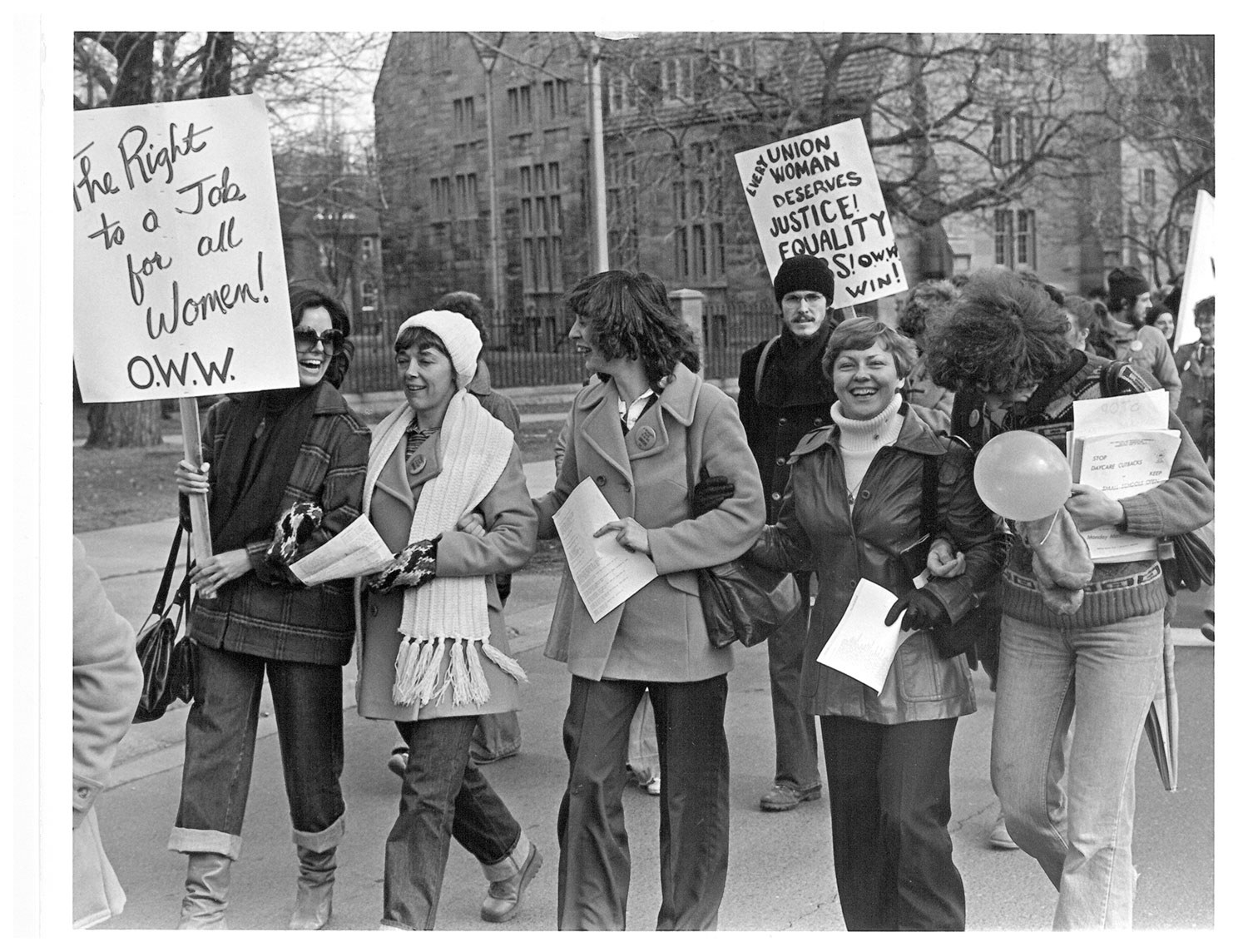

- Women's heritage

The cult of Doris

"Since 2015, the Ontario Heritage Trust has run the Doris McCarthy Artist-in-Residence Program at Fool’s Paradise – a unique, living and working incubator for visual artists, musicians and writers of all disciplines, offering privacy and opportunity for artists to concentrate on their work."

For more information, visit heritagetrust.on.ca/dmair.

Living to 100 is only the latest feat in the life of the singular painter Doris McCarthy, who once cut off her finger for her art

Doris McCarthy turned 100 last week – an achievement the artist’s many friends attribute to the same steely determination that has animated her life. Over those 10 decades, McCarthy has touched thousands as a painter, teacher and mentor of generations of artists. Her greatest life lessons, however, have been through intrepid example: in showing how life can be lived with verve throughout a lifetime and how creativity ripens with age.

Known for her insightful, quick wit and no-nonsense ways, McCarthy is very frail now, confined to bed at Fool’s Paradise, the home she built on five hectares overlooking Lake Ontario near the Scarborough bluffs. “It’s a miracle she made it to 100,” says artist Wendy Wacko, McCarthy’s former student and the producer of the 1983 docudrama Doris McCarthy: Heart of a Painter. “I swear she was holding on just for that.”

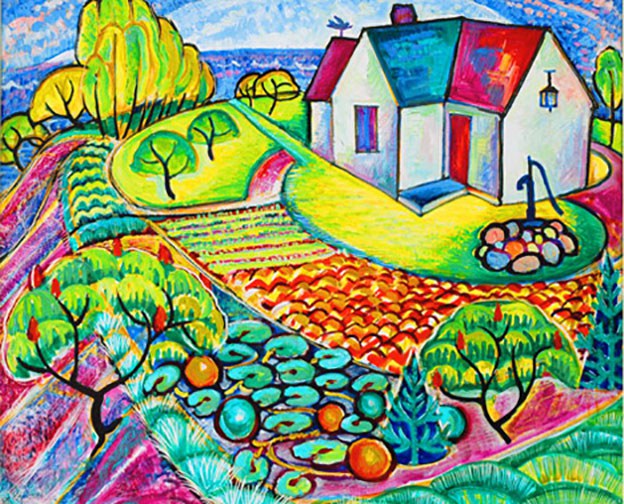

McCarthy’s centenary is being marked by retrospectives of her 75-year career, prominently Roughing it in the Bush, comprised of 70 works, some never before seen publicly, at the Doris McCarthy Gallery at the University of Toronto’s Scarborough campus and the U of T Art Centre downtown. The artist’s long-time Toronto gallery, Wynick/Tuck, is mounting Eight Paintings/Eight Decades, which succinctly captures McCarthy’s broad vocabulary of technique and evolving style.

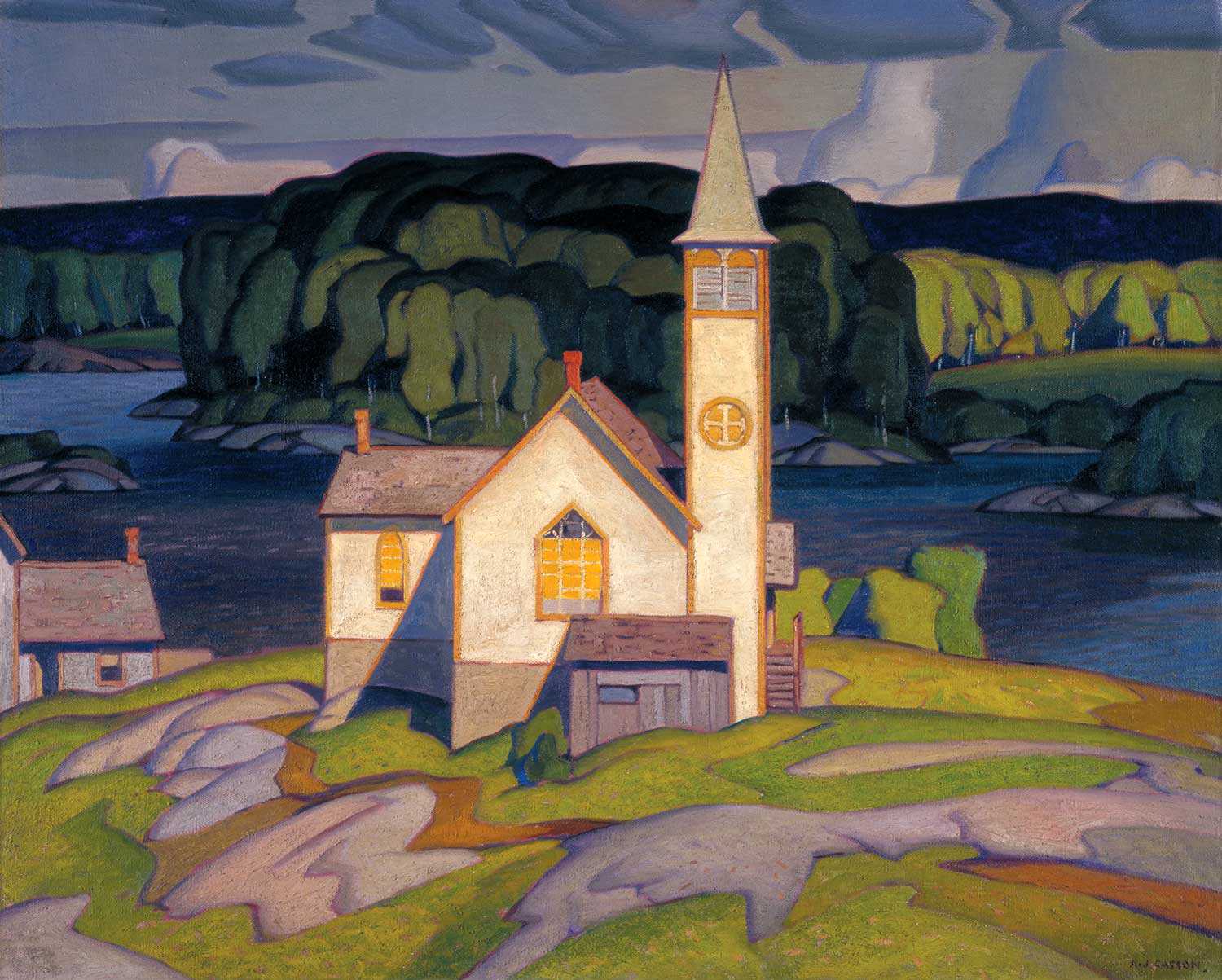

The constant is landscape, which the Calgary-born artist began depicting as a girl growing up in Toronto’s Beaches neighbourhood and cottaging in Muskoka. A scholarship student at the Ontario College of Art, McCarthy studied with Group of Seven painters, among them J.E.H. MacDonald and Arthur Lismer, who offered her a teaching job at the Toronto Art Gallery and, after she graduated in 1930, a position at Grip, the advertising agency where many of the group worked. As a woman, she was expected to work for nothing. Having none of that, McCarthy took a position teaching art at Central Technical High School, where her students included Harold Klunder, Murray McLauchlan and Joyce Wieland, who said McCarthy inspired her to become an artist.

The school, like many of the era, prohibited women from teaching after they married. “Doris said she would have happily stopped, but it didn’t happen,” says Lynne Wynick of Wynick/Tuck. Of the great love of her life, the husband of a friend, McCarthy is discreet, though she once told an interviewer she became closer to his widow after he died.

A prolific painter, McCarthy up to the ’70s showed often at galleries attached to department stores, universities and art societies such as the Ontario Society of Artists, of which she became the first female president in 1964. She chose to ignore the discrimination facing women artists, says Wacko: “She thought the best approach was to do the best job you can and don’t waste time whining about it.” McCarthy is not one to mope. When she realized raising a family wasn’t in her future, she forged ahead – teaching, painting and expanding Fool’s Paradise, which she purchased in 1939 and has bequeathed to the Ontario Heritage Foundation for use as an artists’ retreat after her death.

Retirement in 1972 freed her to paint full-time and fulfill her dream of visiting the Arctic, which inspired the famed Iceberg Fantasy series, her first foray into large-format painting. McCarthy’s energy and work ethic was extraordinary, even into her 90s, says Wacko, who accompanied her on annual painting trips to Ireland, the Alberta badlands, and Italy: “We’d be up by six; if we weren’t out by 8:30, she was cranky.” During one trip to Tuscany, Wacko recalls, McCarthy was horrified when Wacko wanted to waste a morning shopping for Italian hand-painted dishes: “We finally had bad weather and she broke down and said ‘okay.’ ”

Often weather was brutal – so cold that when using watercolours, they had to add glycerine to the water to prevent it from freezing. “McCarthy taught me that,” Wacko says. “You don’t learn that in art school.”

McCarthy painted until five years ago, often precariously positioned on a step-ladder, producing what many regard as her finest work in her last decades. When an arthritic finger became bothersome, she had it cut off. As her eyesight diminished, her technique shifted: “It was far more about shape and tone and colour, less about detail,” says Wacko.

Never did she define herself as elderly. When looking for a gallery to represent her in the late ’70s, she chose Wynick/Tuck, which had a roster of young artists. “She didn’t want to be with the old guys,” says Wynick. In 1989, at age 79, she received a B.A. in English from the University of Toronto and published the first of three well-received memoirs, which contributed to what friends refer to as the “cult of Doris.” When her publisher wanted to use “old woman” in the title of the third, McCarthy prevailed. “I’m damned if I’m going to be old,” she told the Globe and Mail. The book’s final title: Ninety Years Wise.

Even now, despite failing health, her optimistic spirit remains, says Wacko: “She told me, ‘I’m so grateful for this extra time so I can lie in bed and remember all of the great adventures we had.’”

The years brought McCarthy institutional honours, including an Order of Canada and five honorary doctorate degrees. Yet recognition by the art elite – public institutions and historians – has proven elusive, to her frustration. “The National Gallery doesn’t own a thing of mine and it damn well should,” she told the Globe and Mail in 1990.

Since then, the gallery has purchased four works, though only one has been displayed—in a group show about the Arctic. National Gallery curator Charles Hill reiterates the common criticism of McCarthy’s work among academics: it doesn’t forge new ground, it’s imitative, there’s no “shock of the new,” to quote the late art critic Clement Greenberg. “I think it’s responsive, not initiatory,” says Hill, who allows that he has seen most of the work only in reproduction and is not familiar with McCarthy’s later canvases. “I’m not going to say I’m any authority on Doris McCarthy. But what I’ve seen hasn’t interested me.”

Art historian David Silcox, president of Sotheby’s Canada, regards McCarthy as “someone who has always been there.” He hasn’t actively followed her work, perhaps for that very reason, he says: “Maybe I’ve been led not to look as closely or with as much curiosity as one ought.” McCarthy has always been out of step with art world fashion, Silcox notes: “I’ve always noticed there are no females in the Group of Seven,” he says wryly. “But a lot of women were as good.” McCarthy also faced what Silcox calls the entrenched “masculine mystique” governing how the North is depicted in paint.

The fact McCarthy was an older woman – a former high school teacher at that – working in a well-trod idiom led many to dismiss her, says Wynick. The gallery faced flak when they took McCarthy on in 1978, a time when photo-based and installation art was the vogue. “But the quality won us over,” she says.

McCarthy was well aware her work was out of fashion. “My paintings are so legible, I feel guilty,” she joked to the Toronto Star in 1999. Not that she gave a fig: “Most artists make the mistake of feeling they should be doing what other artists are doing instead of what they do best.”

“She’s always been out of style except for those people who buy her paintings,” says Toronto collector Alan Bryce, who bought his first McCarthy in 1987. Over the years, McCarthy’s prices have risen slowly but steadily, as she amassed an avid following. In 2008, her 1964 oil Home fetched $57,000 at Sotheby’s in Toronto, a record price for her work at auction. (Prices at the Wynick-Tuck show range from $950 for a woodcut to $68,000 for an oil.) Bryce says he tried to summon interest for a retrospective at the National Gallery, with no luck. “Doris once said she’d stay alive to see that show,” he says.

McCarthy was thrilled that her namesake gallery was mounting Roughing it in the Bush, reports guest curator Nancy Campbell, who unearthed never-shown hard-edged abstracts from the ’60s and early ’70s, which she has masterfully mixed with works from other periods. The experience left her with a new appreciation of McCarthy’s work, Campbell says. “I want people to see that she really did have a unique place in the lexicon.” But were it not for McCarthy’s longevity, the show would never have happened, Campbell believes: “Would we be looking so closely if she had died 20 years ago?” The answer, of course, is no. Which means that even at age 100, Doris McCarthy is still delivering art lessons. [Published by Maclean’s on July 20, 2010. Used with permission of Rogers Media Inc. All rights reserved.]

![“Mayor Oliver: Wonder who told them we didn’t encourage the suffragette movement in Toronto?”, [photograph], ca. 1910, Newton McConnell fonds, C 301-0-0-0-996, Archives of Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Archives-of-Ontario-cartoon-I0007312-web.jpg)

![F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/27790_boy_and_woman_520-web.jpg)

![Wyland, Francie. 1976. Motherhood, Lesbianism, Child Custody: The Case for Wages for Housework. Toronto: Wages Due Lesbians. Cover woodcut by Anne Quigley. CLGA collection, in monographs, folder M 1985-054].](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Wages-Due-Lesbians_Wyland-pamphlet-image-web.jpg)