Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

The evolution of the panto

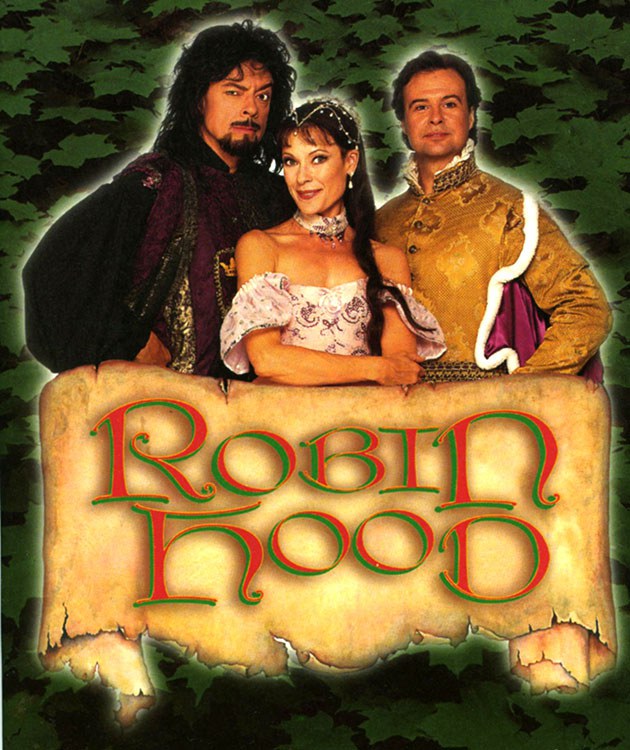

It is always entertaining to watch a troupe of actors sing, dance and throw their audiences into hysterics. This is something we witness every year at the Elgin Theatre when Ross Petty Productions repackages a classic fairytale and offers up a comedic pantomime that leaves audiences rolling in the aisles.

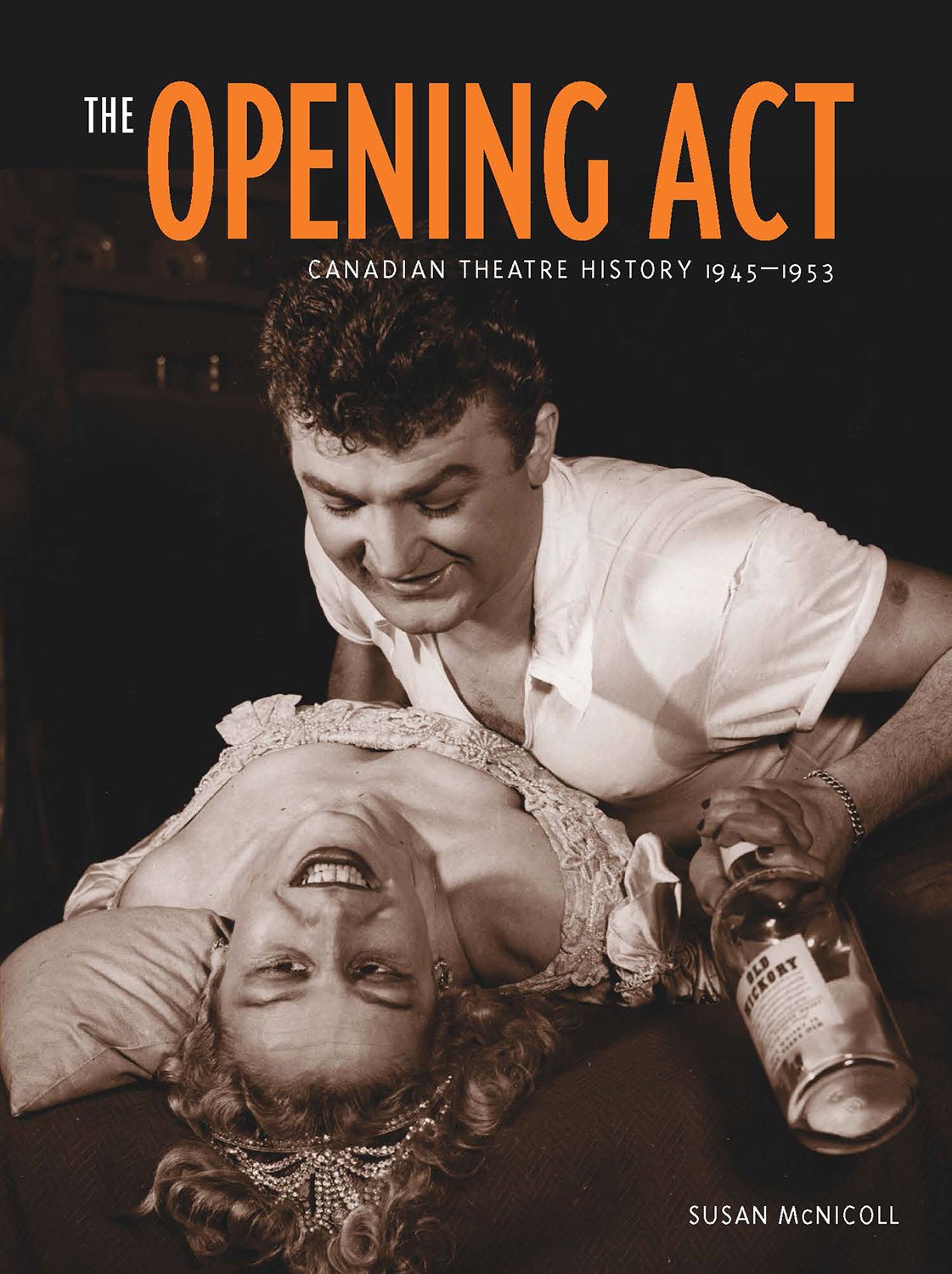

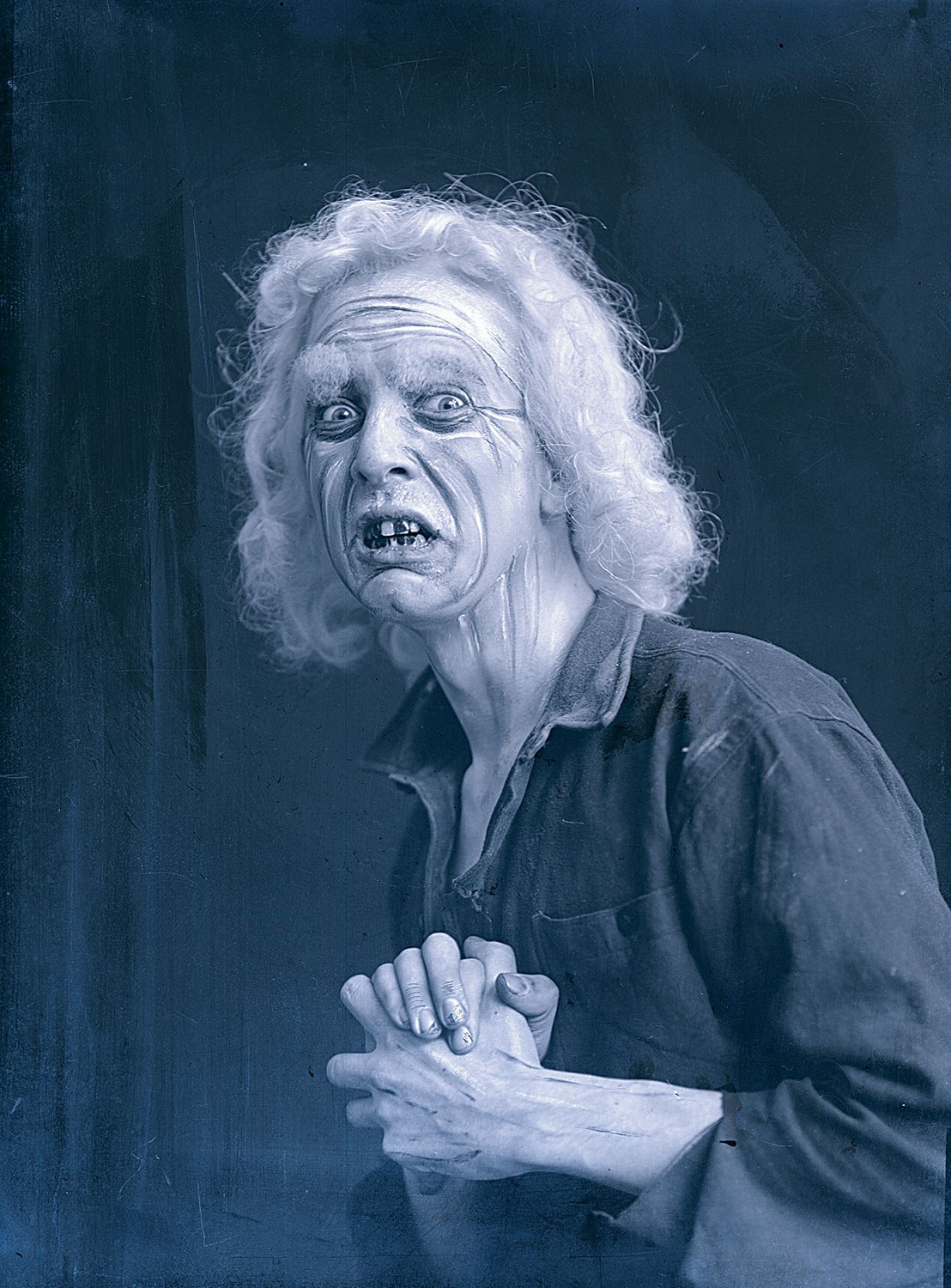

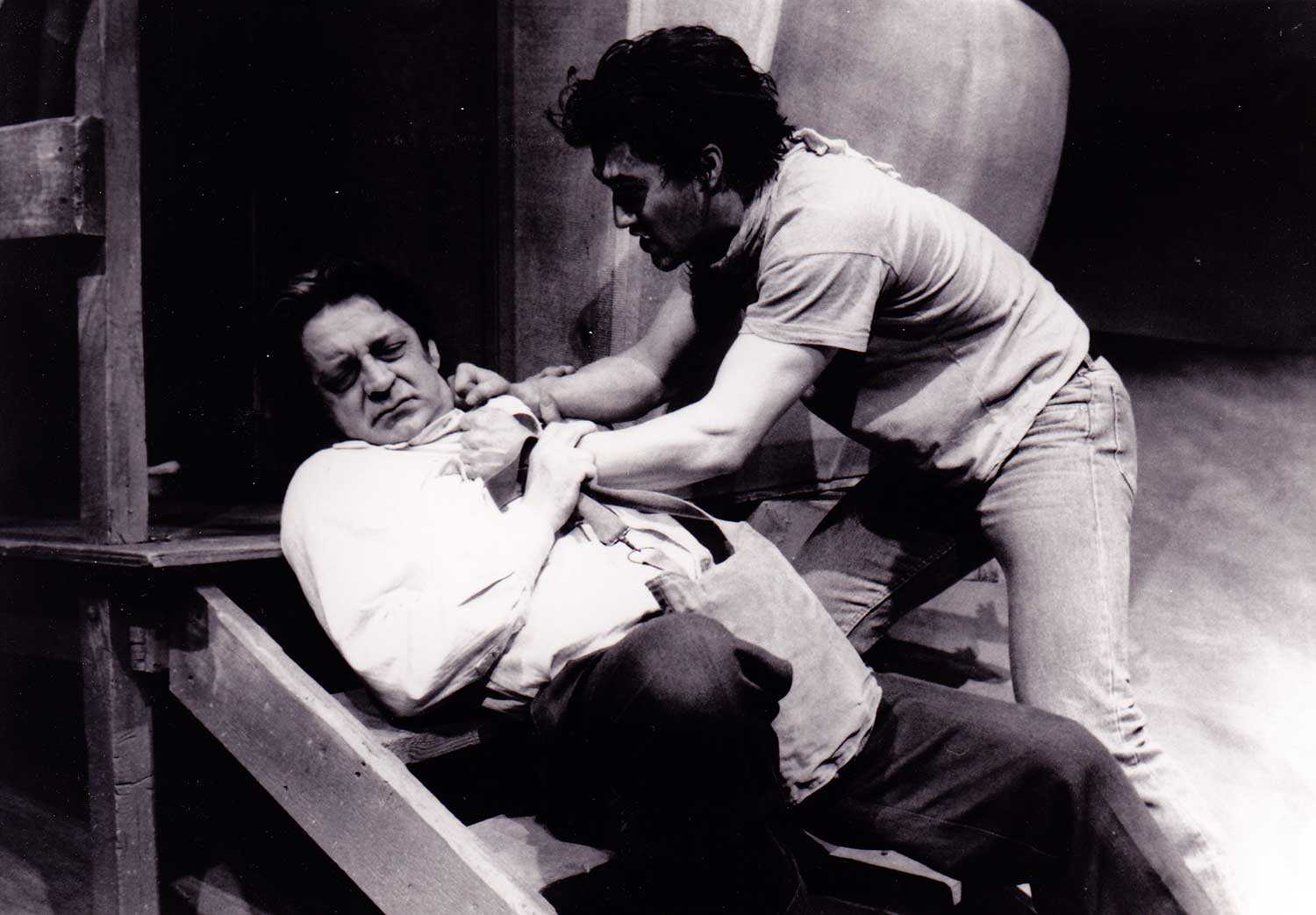

The pantomime – or panto as it has become known – has been making people laugh for generations. It is a theatrical form with a long history of slapstick, bawdy humour, cross-dressing characters and often raucous audience participation. Grounded in classical theatre, there is evidence of pantomime having been performed in ancient Greek and Roman times. Today’s panto takes elements from the Italian commedia dell’arte (several of the characters – Harlequin and Columbine – and traditional comi-tragic storylines still resonate in modern pantomime), mummers’ plays from the Middle Ages (British folk plays performed at holidays with both religious overtones and the coarse humour and stage fights we associate with pantos today), and 16th- and 17th-century theatrical forms. One can argue that Shakespeare himself – who was so fond of putting characters in gender-bending roles facing often outrageous plotlines – was drawing on the traditions of pantomime.

The panto that we see on world stages today has been fine-tuned largely by the British, who, in the 19th century, replaced some of the classical tales with increasingly popular European stories. Celebrity actors of the time, David Garrick and Joseph Grimaldi, transformed the pantomime into a hilarious clowning phenomenon. With comic antics to entertain both young and old – and bawdy language to provide secret guffaws for the adults – the panto became an annual tradition that has, over the years, helped define the British sense of humour. Even gripping events in the daily press – like the 1605 Gunpowder Plot (the attempted assassination of King James I) – spawned pantomimes that wove the story of Guy Fawkes into the national consciousness.

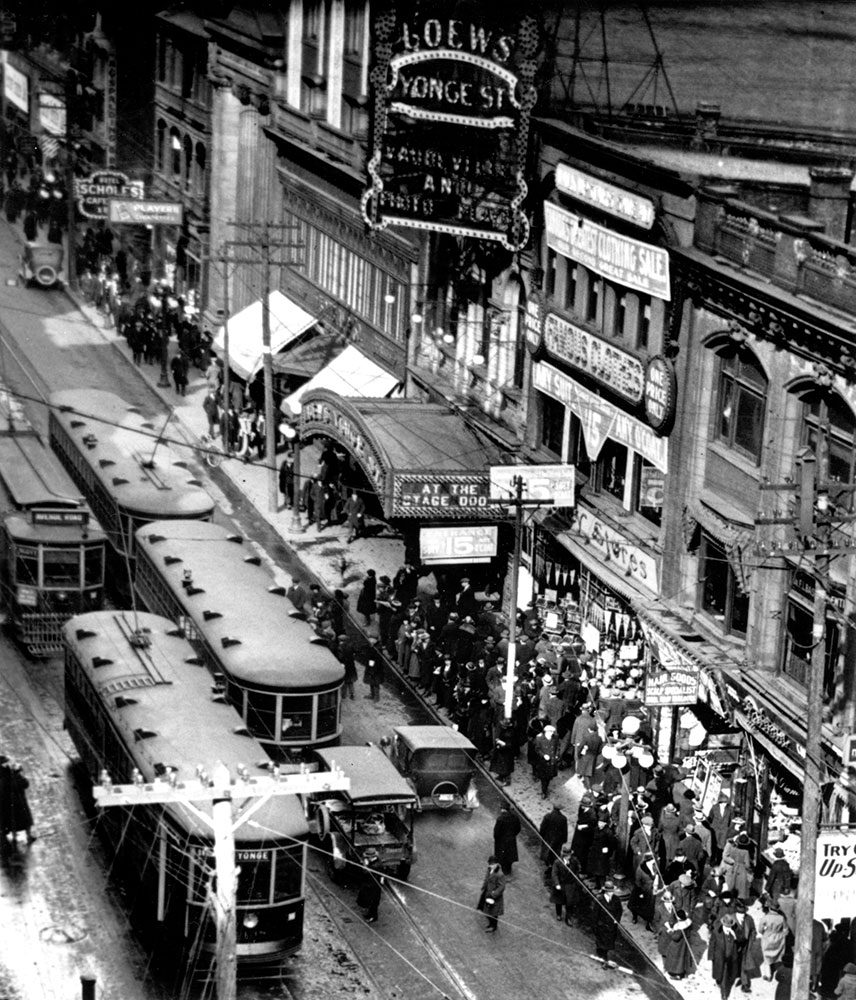

In Ontario’s theatrical history, pantomimes have played their parts in shaping our theatrical landscape. Toronto’s Royal Alexandra Theatre opened in 1907 – and its opening play was, not surprisingly, a pantomime. When the Orillia Opera House was nearly destroyed by fire in 1915, the subsequent rebuilding and reopening in 1917 was marked by a pantomime. And now, since 1996, Petty’s annual panto at the Elgin Theatre has become an anticipated part of the holiday season for many.

“The popularity of panto,” notes Petty, “comes from the unique element of audience interaction with the performers and ad libs about daily news events. There’s as much entertainment value for adults as for children.”

The modern pantomime continues to be an important part of our theatrical repertoire. And given the popularity of these annual productions for celebrities who clamour for an opportunity to bring “play” back to the stage, the panto shows no signs of disappearing – despite all the “boos” and “hisses.”